A mountain breeze stirs the willows. Bees seek out the primroses and a frog slips into the pond from a lily, while the coin-spinning call of a wood warbler mingles with sounds of hammering and laughter from the workshops.

Welcome to Centre for Alternative Technology (CAT), home of the Zero Carbon Britain research project.

What is the Centre for Alternative Technology?

CAT’s most recent Zero Carbon Britain report, Rising to the Climate Emergency, suggests how we could reduce greenhouse gas emissions to zero by using technology we already have and by changing the way we use land. It is calm, rational and inspirational, but then that is what you’d expect from CAT. People have been working on practical solutions to environmental problems here since 1973, when a few “crazy idealists” settled a derelict slate quarry.

Demonstrating the flexibility that made it resilient, the community evolved into a visitor and education centre to accommodate the crowds that rocked up, as word spread, to see solar panels for themselves. Today, a management hierarchy has replaced the flat structure, and visitors are no longer blown away by the sight of a wind turbine. But there’s still plenty to see and do, especially in school holidays when there are children’s activities and tours.

Related articles

Zero carbon pioneers

The site may be a little scruffy in places; after all, it is more living laboratory than purpose-built visitor experience. But it has demonstrations of renewable energy, sustainable buildings and waste-water treatment.

The mole hole continues to terrify small children. And the gardens, in their lush and gaudy profusion, are a place of solace and contemplation. Look no further than this rain-haunted quarry, marooned among conifer plantations and sheep farms, for confirmation of the Zero Carbon Britain message that our land and soils can be more productive and biodiverse.

It is hard to imagine how barren this slate tip looked over 40 years ago; now, salad grows all winter long, flowers bedazzle, dragonfly nymphs cling to reeds, frogs croak, bats roost, beans thrive, pumpkins grow plump and, sometimes, otters take fish from the lake.

CAT is open for day trippers, but be sure to browse the website (cat.org.uk) before visiting. Wise up on Zero Carbon Britain, arm yourself with questions for the information office, join a guided tour, book accommodation if you like, and get discounted entrance if you arrive by public transport.

You can also sign up for a short course (see box page 88), a Masters course at CAT’s Graduate School of the Environment, or even volunteer.

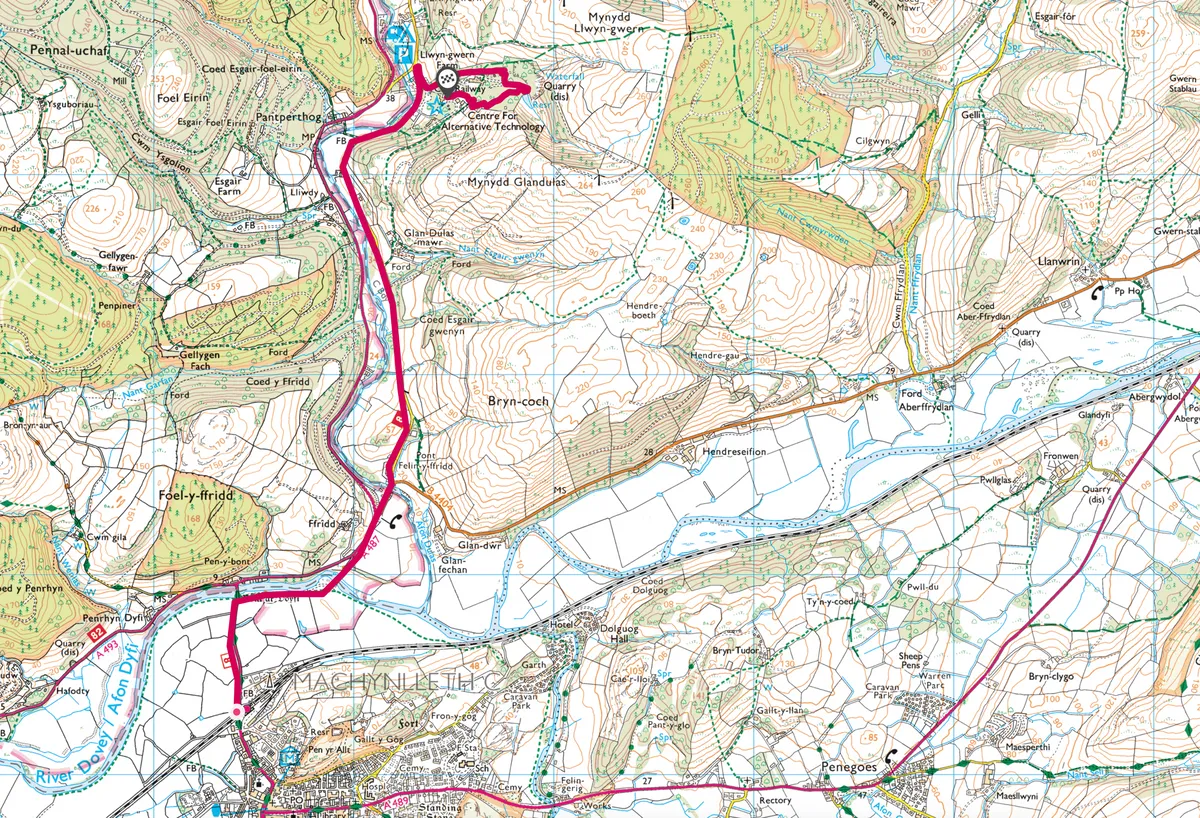

Walking route from Machynlleth to the Centre for Alternative Technology on the edge of Eryri (Snowdonia) National Park.

1. Biosphere reserve

Turn right out of Machynlleth station (or take the 34/T2 bus). At the Dyfi Bridge, take the river path right then cross the Millennium Bridge and follow National Cycle Network (NCN) 8 on a quiet lane parallel with the A487 for just under three miles to CAT. The entire Dyfi River catchment is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

2. Power of water

Pay at reception, then either walk up the Garden Steps, or take the water-and-gravity powered funicular railway. A full tank of water in the descending carriage pulls the lighter carriage up, before releasing its load into the stream at the bottom, while the one at the top is filled. Decide whether to explore CAT before or after walking the Quarry Trail, which circumnavigates the site. The Quarry Trail begins outside the restaurant.

Head uphill into the woods, passing the Hairy Hut, one of many experimental structures designed and built by students on CAT’s Masters courses. Plant-based construction materials, including straw, hemp, timber and cork sequester carbon in the building’s fabric.

3. Quarry creation

At the view into the quarry, scan the scarred cliffs for ravens and peregrine falcons. At the southern perimeter of the Snowdonia slate zone, Llwyngwern Quarry ceased to operate just 20 years before CAT was founded. The slate was formed millions of years earlier on the bed of a warm shallow sea, from mud that was subsequently crushed and heated by movements in the Earth’s crust.

4. Fruits of the land

Originally built to supply the quarry, the reservoir now provides CAT with rainwater borrowed on its journey downhill. It is filtered through sand and treated with ultraviolet light for drinking, produces electricity by powering a 3.5kw micro hydro turbine, and tops up the lake created to feed the cliff railway.

Try a short course at CAT in 2020

- Social Forestry, 31 March–3 April

- Eco Refurbishment, 17–20 April

- Earth Oven Building, 18 April

- Bird Identification, 24–26 April

The path follows a contour high up the slate tip. In the gardens below, fruit and vegetables ripen on 40 years of compost, but up here biodiversity has been lightly managed, allowing it to thrive. All the stages of ecological succession are evident: the pioneering mosses, lichens and willowherb, giving to perennials such as foxgloves and heather, succeeded in turn by the woody scrub of thorn and bramble, which protect the young birch and rowan, Scots pine and oak.

There is nothing like a mountain to put things into perspective. With views over forested slopes to Tarren y Gesail, it is hard not to see our human endeavours within the context of geological time. That we have inflicted so much damage in such a short period is abhorrent. But we can draw strength from those seeking solutions.

5. Eco education

Drop through hazel coppice and wildflower meadows to the visitor site, and get involved with a mix of hands-on displays and real-life examples, such as composting and rammed-earth buildings. Find out how electricity is made from waves, how a solar panel works, or how much water it takes to grow 1kg of chickpeas compared to 1kg of beef.

Nowhere, of course, is flawless and occasionally, even CAT sometimes struggles to practise what it preaches (as I know from my time on the staff). But there is plenty to draw strength from in this venerable eco-centre, surviving where others have fallen by the economic wayside. Like the pioneering plants on the slate and beans growing ripe in the field, it is still a source of hope.

Map

Machynlleth to Centre for Alternative Technology walking route and map