Our history guide relates the tales of ancient spiritual heroes and travels to a remote Welsh valley where a holy guardian of nature once lived and the part they played in All Saints' Day.

What better time of year to explore the more tranquil corners of these islands, seeking out these mystical figures from the dawn of Christianity, than All Saints Day?

These days, Halloween celebrations are more or less over in one night. But in the Christian calendar of centuries past, Halloween was just the beginning of three days of commemoration as part of a religious event known as All Saints' Day. Our history guide looks at the history and traditions of this Holy day.

When is All Saints' Day?

Central to All Hallowtide, as it was known, was All Saints or All Hallows Day traditionally taking place on 1 November.

What is All Saints' Day?

It was, and is, the day to remember all saints and martyrs, known and unknown, throughout Christian history and provides a contemplative contrast to today’s Halloween candy and thrills. Concluding with All Souls Day on 2 November, when priests encouraged their flock to pray for the souls of the departed, All Hallowtide encompassed a glorious mishmash of traditions, both Christian and pagan. The common thread was the belief that a powerful spiritual bond connects us with our ancestors.

What are the Pagan origins of All Saints' Day?

Launched in the year 609 by Pope Boniface IV, All Saints was originally held on 13 May, until Pope Gregory IV moved it to 1 November in 837. Gregory may have been attempting to smother pagan rituals still held in the autumn. But the rituals proved persistent.

For ancient, pre-Christian Britons, early November had marked the beginning of winter. Bonfires had been lit on hilltops, from which domestic fires were kindled. The souls of the departed were believed to visit their old homes.

Eventually the Romans introduced Christianity, which became the official religion of the Empire in 380. But old traditions were well entrenched. By the ninth century, All Saints Day had become merely another thread woven into this tapestry of tradition. This was hardly surprising. Before the 16th century, when Bibles were first published in English and Welsh, parish priests interpreted Latin gospel for largely illiterate rural communities, many of whom went to church just once or twice a year. Christianity coexisted with folk beliefs, some of which persist to this day – apple-bobbing, trick-or-treating and mask-wearing all have roots in All Hallowtide’s pagan origins.

Yet in medieval Britain, the cult of saints was powerful, too. Role models of Christian virtue, they were the superheroes of their day. Some early saints – the martyrs – had chosen to die rather than reject their faith.

Even the relics of these saints held special power: their bones, hair, clothing or other personal effects. Saints were believed to be able to petition God on behalf of devotees, and pilgrimages were made to places associated with them. Although Henry VIII’s Reformation (1529–1537) largely stamped out their cult, saints too had become deeply rooted. Thus,

like Halloween, All Saints Day also endures.

Why do we celebrate All Saints' Day?

Nowadays, churches hold All Saints Day services in which worshippers light candles to commemorate all the saints and martyrs who once excited people to holiness. We’re talking a lot of saints here. Some, such as Mary, Paul and Peter, sound familiar. But long before the Catholic tradition of canonisation began in the 10th century, Britain had hundreds of home-grown saints, memorialised by a plethora of holy wells, caves and churches still to be found in quiet corners of the British countryside.

So who exactly were these early saints?

Rewind to the Romans. Christianity had dwindled after their retreat in 410. British pre-Christian pagan beliefs lingered and pagan Anglo-Saxons were settling what would become England. Then one man crossed the sea from France to help reinvigorate Christianity: Bishop Germanus, sent by the Pope in 429. He soon inspired Dyfrig, a scholar who spread the word in south-east Wales. Dyfrig’s successor Illtud established a college at Llanilltud Fawr (Llantwit Major) attended, over time, by some 2,000 Christians of largely Celtic-speaking regions of Britain.

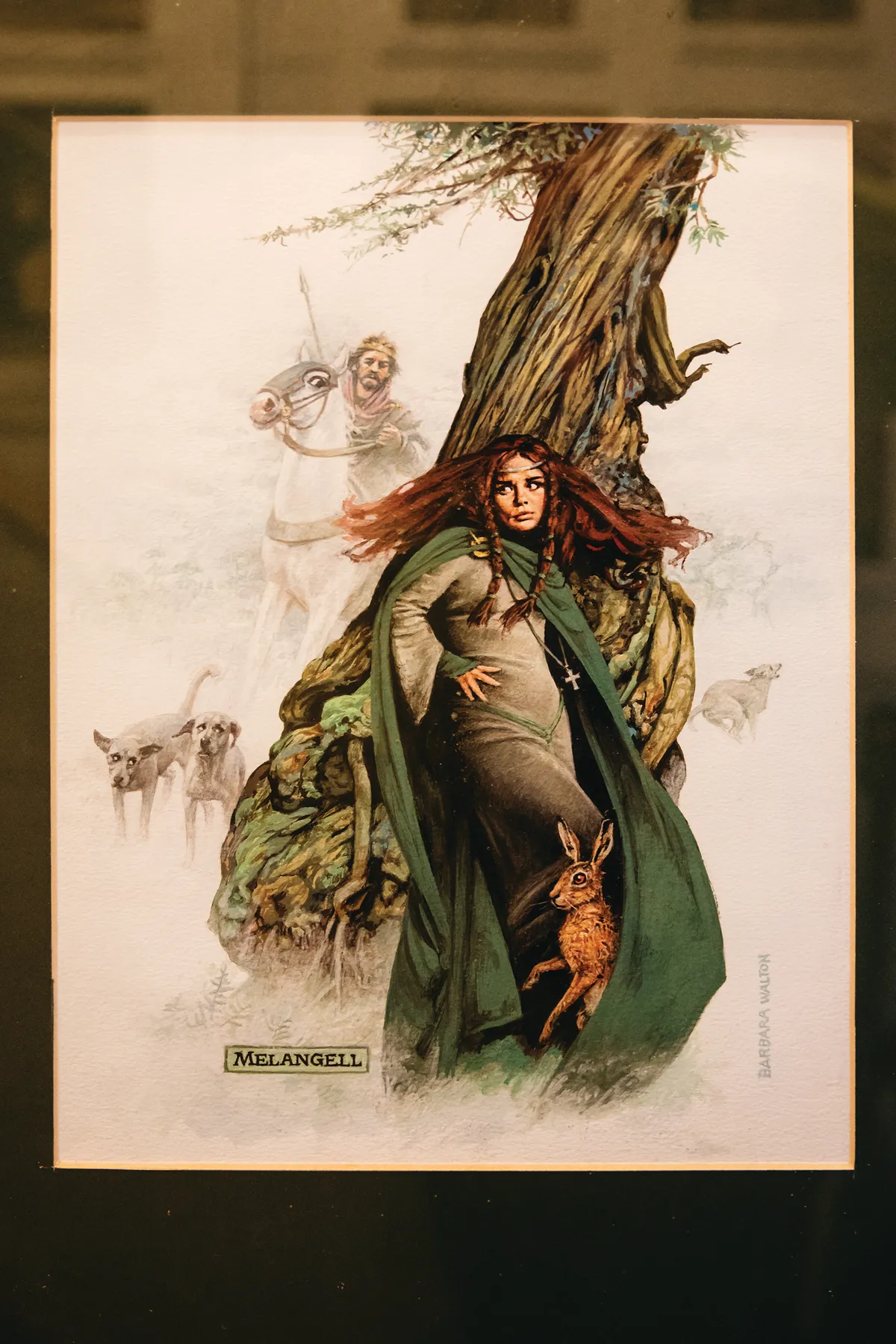

Throughout the fifth to seventh centuries, dozens of Christians travelled in small wooden boats between Ireland, Brittany, Cornwall, the Isle of Man and Wales. They founded monasteries – self-sufficient communities devoted to prayer, learning and hard labour. Occasionally a monk or nun left the monastery in search of wild places – islands, caves, fens or forests – where, as hermits, they felt closer to God. These men and women were considered holy and were referred to as saints. Whatever our own beliefs, perhaps All Saints Day is a good time to remember these courageous people who brought messages of peace. Among their number is Melangell, patron saint of hares.

Deep in the heart of a green valley in the Berwyn Mountains, surrounded by gnarled and fissured yews, lies a tiny church. This simple stone structure, built almost 1,000 years ago, is dedicated to a little-known saint once revered for her love of nature. Inside is the oldest Romanesque shrine in northern Europe – a shrine said to harbour the relics of that saint. Her name? Melangell.

Like many other saints, Melangell’s tale is remembered by few these days.

Champion of nature – the story of Saint Melangell

Born a princess, Melangell is said to have fled across the sea from her home in Ireland to escape an arranged marriage. She found refuge in the remote Cwm Pennant. On a pleasant day, with rooks and red kites carving arcs in its sky, wrens singing and squirrels traversing the trees, you get some sense of the tranquillity Melangell found in this Powys valley.

She had lived as a hermit in Cwm Pennant for 10 years when Prince Brochwel of Powys came hunting in 604. According to a 15th-century document, Historia Divae Monacellae: “His hounds pursued a hare into a bramble thicket where they found a beautiful virgin at prayer. The hare took refuge under the hem of her garment and the dogs fled, howling.”

Impressed, Prince Brochwel granted her land to create sanctuary in perpetuity “for any person or animal in need”. So Melangell founded an abbey.

The abbey has now gone, but the church survives. And the tradition of sanctuary remains, with the church door creaking open on a regular basis to admit hikers, tourists, locals and pilgrims from across the world, of any or no faith.

“They are drawn to Melangell by her compassion, courage, and perseverance,” Reverend Christine Browne tells me. “It’s lovely here but the rain is plentiful, and I often wonder how she managed the cold and fog and dark of winter without the central heating I rely on.

“She refused Brochwel’s order to hand over the hare; that was a courageous thing to do, especially for a woman. And running the abbey can’t have been without challenges, though it must have been a joyful offering or people wouldn’t have sought her out in the way that they did.”

With pheasant shoots throughout winter, Cwm Pennant is no longer a place of sanctuary if you’re a pheasant, an irony not lost on the Reverend. Christine, however, has to consider all who use the valley, her challenge being to interpret Melangell’s message through peace, harmony and finding common ground.

Perhaps Melangell’s courage was less complex. Stand up against violence though she did, as a hermit she was answerable only to God and herself. Nevertheless, it is tempting to wonder how she, and the other ancient saints, would address our current conflicting interests.

Other saints through history

Cennydd 6th century

Cast adrift as a child, Cennydd was allegedly rescued and raised by gulls on Burry Holms, Gower. At his church in Llangennydd, near Crickhowell, a giant gull is hoisted up the tower every 5 July. A stained-glass image of Cennydd can be found at St Gabriel’s church, Swansea. Llangennith, Swansea SA3 1HU

Máelrubai / maelrhubba 642–722

An Irish saint who founded a monastery in Wester Ross, Máelrubai later became a hermit on Isle Maree before being killed by Vikings. His holy well survives. Hire a kayak to visit the island on Loch Maree. visitscotland.com/maelrubai

Maughold d. 488

Legend has it that Maughold was an Irish bandit who was converted by St Patrick before crossing the sea to the Isle of Man and living a devout life in a cave. His church contains important Celtic crosses and an ancient holy well. visitisleofman.com/maughold

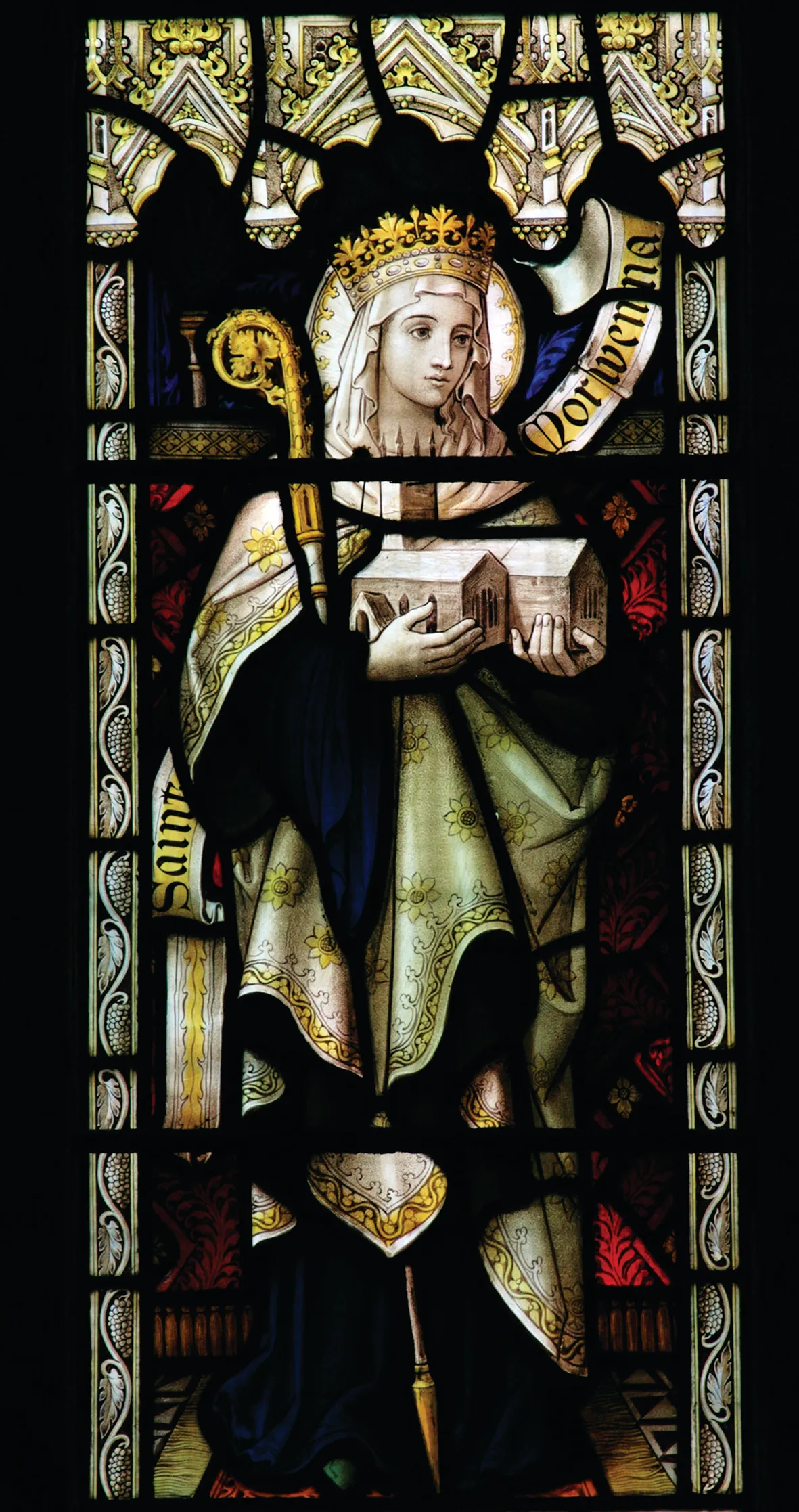

Morwenna 6th century

Morwenna was a Welsh princess who trained in Ireland before sailing to Cornwall, where she built a church for local people by hand. Her church and holy well are at Morwenstow, where she appears in a stained-glass window. chct.info/histories/morwenstow-st-morwenna-st-john-the-baptist

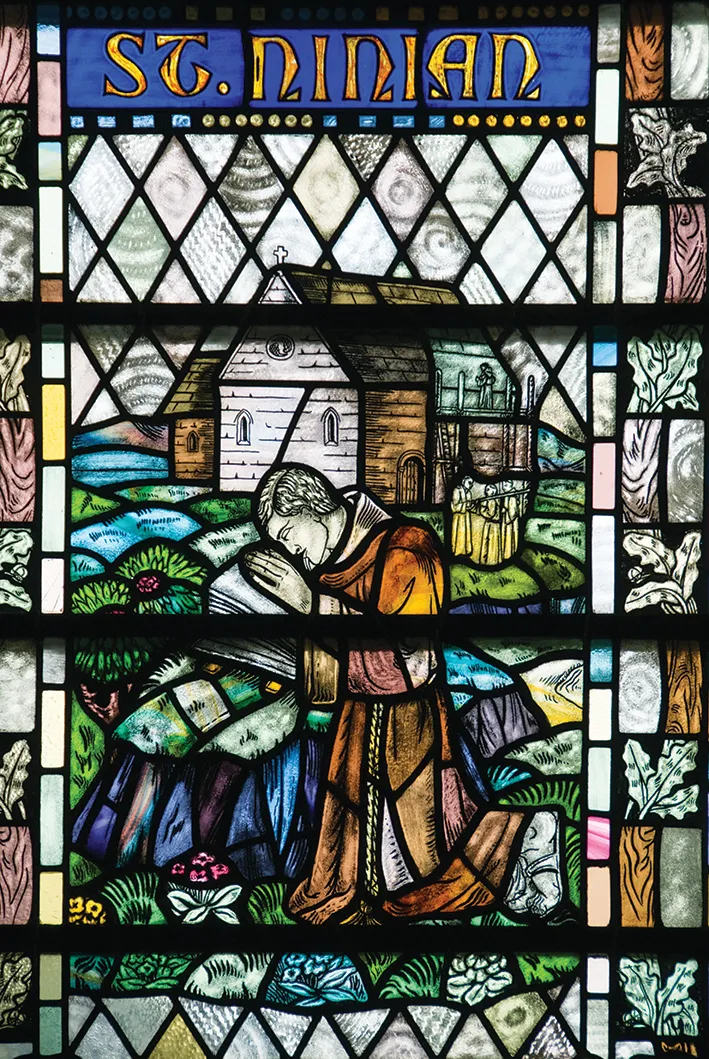

Ninian d. 432

Ninian evangelised the Picts of Scotland and northern England, inspiring dozens of dedicated chapels. Many can be visited on the 250-mile St Ninian’s Way from Carlisle to South Queensferry. St Ninian’s Priory Church, Whithorn holds a stained-glass image of the saint. britishpilgrimage.org/portfolio/st-ninians-way

Non 5th–6th century

St David’s mother Non became pregnant after being raped. Her chapel – apparently built on the site where she gave birth to David – stands near Caerfai on St David’s Head in Pembrokeshire, while nearby is her holy well, regarded as one of the most sacred in Wales. stnonsretreat.org.uk

Julie Brominicks is an outdoors writer who lives in Wales and specialises in landscape and sustainability. Julie feels an affinity with the solitude-seeking lives of those early Christians, if not with their saintliness!