Is there a special place where you feel close to nature? That’s what we asked budding writers this year, for the 2022 BBC Countryfile Magazine New Nature Writer of the Year award.

We received many inspiring entries from aspiring authors – including a moving childhood memoir from our winner Elizabeth Stanforth-Sharpe and three luminous stories from our runners-up Rhiannon Law, Katherine Ilett and Vanessa Wright.

Three further contributors particularly impressed us – our highly commended entries, in which Amy Fox sees a patch of wild land though a child’s eyes, Jennifer Jones writes in tribute to a precious wildlife refuge on the banks of the Mersey, and, first of all, Jo Cross remembers the power of songs sung around a campfire in Devon woodland. Well done to all three.

I hope you enjoy their stories.

New Nature Writer of the Year 2022: highly commended (one of three)

Songs of the Wood

By Jo Cross

The Deer Lodge was a rustic affair of beams and poles draped in tarpaulins, arranged in a circle around a central campfire. It appeared to float, an island in a lake of bluebells – drifts of violet-blue broken occasionally by the groove of a path or clump of bracken. We perched inside out of the sun on upturned logs. Overhead, nailed to the rafters, animal skulls watched over us through eyeless sockets. We were song-makers – come together on this patch of wild Devon land to find inspiration and to sing.

Sometimes, I think nature is the key in which I write my songs – a world rich with analogies that give form to my thoughts. My repertoire of home-made songs tells of estuaries, the first swallows of spring, the rain, the moon, the heather and the gorse and, when a darker mood takes me, rising sea levels, lost wonders, anarchic seasons. It was hardly surprising then, that I was drawn to an immersive music-making experience; time spent feeling the pulse of the land and transcribing into song.

I was drawn to an immersive music-making experience; time spent feeling the pulse of the land and transcribing into song

Months earlier, deep in a torpid winter lockdown, signing up for these five days of communal living had seemed like a desperate act of hope and folly – hard to imagine what it might feel like to be mingling with unfamiliar companions. But we were wild camping, en plein air and off-grid and it felt vibrant. We had emerged from our winter retreats like lizards awakening from a long hibernation, blinking in the light, grateful for every new sensation.

Our campsite was a 62 acre stretch of rewilded woodland on the margins of Dartmoor. Formerly a sterile plantation of larch, this re-imagined landscape of native broadleaf trees, rides and secret pathways was transforming into an abundance of diversity. Rewilders take the long view: let nature lead and life will follow, they say.

That morning we had risen early. Rubbing sleep from our eyes and craving our first mug of coffee, we gathered beneath the canopy of the beech grove and stood, eyes shut, listening to the wood. As our ears tuned in, the stillness that had at first seemed so absolute, became a polyphony of sound: creaking branches, the hustle of a squirrel, a blackbird’s fluting alarm call, a wood-pigeon’s five note refrain. It was cool in the shade of the beeches, no warmth perceptible yet from the pale sun. I blinked my eyes open and tilted my head back to look up at the auditorium around me. A shaft of light was just catching the uppermost branches, the leaves luminous against the sky.

We’ve grown accustomed to noise – it’s the soundtrack to our lives: the hum of tyre on tarmac, the rumble of aircraft, the beep-beep-beep of a reversing truck, the booming bass from a passing car, the tractor, scooter, jetski, mower. Noise is so pervasive, we’ve forgotten how to listen, really listen. When the pandemic stopped us in our tracks, taking us off the roads and out of the skies, the country suddenly discovered birdsong – as if it hadn’t always been there in the background, the silver beneath the tarnish. It seemed that everybody was talking about it, writing and tweeting about it, recording it. I’ve read somewhere that birds have learnt to sing much louder in our cacophonous motorised world. For those few silent months, however, the birds sang unopposed - and the people listened. Birdsong became the salve of the world’s wounds.

Later, gathered around a crackling fire, we sat soaking in the soundbath of the nightjar – a persistent, pulsating two-tone purr that permeated the air around us. Impossible to tell which direction the call came from and little chance of catching even a glimpse of this reclusive bird of the darkness. But we were content to listen and to marvel at how the nightjars had navigated their way to this plot of land – discovering for themselves a welcoming habitat with its tapestry of tree cover and cleared glades.

As the fire faded, we shared our songs, singing together in the moonlight. It is thought wolves like to sing, the bonding-round-the-campfire sort of singing, their social glue. Not howling at the moon, but singing. The world needs more of it.

What the judges said

Gillian Burke: "This was a unique entry with the focus of the writing wishing to draw the reader to listen and hear to the sounds of nature, through the written word. The writer didn’t have a long history with the place, so the sense of connection came from a feeling of refuge and peace from the noisy motorised world. I loved being reminded of our natural human sounds - our voices and songs can be a part in the natural world."

A biologist, Gillian presents the BBC’s Watches series. She also writes a column for our sister magazine BBC Wildlife.

Nicola Chester: "A really different perspective, writing about the process of making music, immersed in and inspired by a place. Nature as auditorium, hearing 'the silver beneath the tarnish' of noisy human activity, the sensory 'soundbath of the nightjar'. Lovely."

Nicola is the author of On Gallows Down, winner of the Richard Jefferies Award for the best nature writing published in 2021.

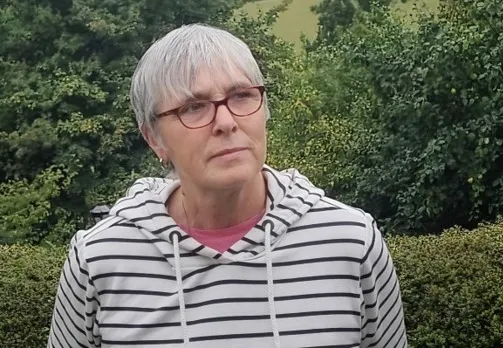

Meet our first highly commended nature writer, Jo Cross

Name: Jo Cross

Age: 64

Based: On the west side of the Malvern Hills

Work: Retired.

How can time in nature inspire you to make music? Music is all around us – time in nature can help us to really listen.

What inspired you to write about nature? I think I express myself through nature – it is how I make sense of the world and my feelings about it.

Have you ever trained in nature writing? I have just completed the Certificate in Creative Non-Fiction with the Institute of Continuing Education at the University of Cambridge and will be continuing with the Diploma in October. Nature writing is an element of both courses.

Would you like to do more nature writing? I will certainly keep writing about nature – both prose and songs. I would just like to keep honing my writing skills, finding ways to express the experience of being out in the natural world.

What are your favourite places to enjoy nature and landscape? I am fortunate to live in a very beautiful part of the country, but for me there is no better place on this earth than the west coast of Scotland.

New Nature Writer of the Year 2022: highly commended (two of three)

Plants Brook

By Amy Fox

There’s a housing estate on the edge of Birmingham where tributaries of tidy, pink-bricked houses flow sedately down one side of a small valley.

When the original farmland was portioned up for development, one slice was preserved and became New Hall Valley Country Park. I’m walking here with eight-year-old Joey and five-year-old twins Danny and Jake.

An alleyway takes us to a patch of grass dotted with daisies: tiny weathermen who clasp their petals tightly over their heads when it rains and open them wide to embrace the sunshine. One edge is bordered by fences, the other by a clump of wild plum trees. A few weeks ago, their clouds of buzzing white blossom smelt of spring; now they’re draped with green and red and when we part the leaves we find plums forming: green and hard as fists but some already starting to blush with the promise of what’s to come. In a few more weeks the children’s fingers, faces and pockets will be sticky with juice.

An alleyway takes us to a patch of grass dotted with daisies: tiny weathermen who clasp their petals tightly over their heads when it rains and open them wide to embrace the sunshine

We enter a scrap of ancient oak wood. The sunlight through the new spring leaves creates an emerald city for us to explore, buttressed by twisting beams and archways hung with ivy tapestries. The woodland floor is awash with cow parsley: under our feet, towering over our heads and leaning across the path so it brushes our arms and faces, filling the air like confetti until we seem to inhale it; the warm, soft scent of May filling our noses, mouths and lungs. The woods have been white for some time: before the cow parsley there were delicate crosses of garlic mustard flowers, now evolved into embryonic seed pods reaching skyward like thin, witchy fingers; soon will be the turn of the sturdier hogweed, its knotted stems already starting to untie. In autumn, when the woods have turned bonfire bronze, these dried-out, hollow stems will become telescopes, pea shooters and kazoos.

Speckled wood butterflies dance to an accompaniment of birdsong: the background bubbling of blackbirds and robins punctuated by the assertive whistle of a nuthatch, the urgent burst of a wren, the headlong rush of a chaffinch. The great spotted woodpeckers are no longer drumming; we imagine them inside every hole we spot, but the oaks keep their secrets.

We cross a road and reach a sloping meadow. Buttercups pour down the hill in a torrent of gold, interrupted by jewel-like clumps of red clover and sorrel. Tares creep unobtrusively amongst the stems, peeping modestly under violet bonnets, while plantain flowers stand tall: slender May queens with crowns of tiny petals. The children break into a run and race down the hill as if pulled by gravity or the sheer joy of open space.

Halfway down, Danny and Jake throw themselves into the arms of a young oak – a well-known and trusted friend – and climb, while Joey sits and watches a soldier beetle wander up his leg. We see green woodpeckers here sometimes, their undulating flight and witch’s cackle unmistakeable, but today there’s just the clap of the wood pigeons taking off from the trees at the bottom of the hill.

Late in the summer, when the grass is shoulder-high and warm and smells of hay, the children will play at making hares’ forms: lying down, rolling over and losing themselves in its softness. At the bottom of the hill there’s a scattering of mossy logs which become charred with candlesnuff fungus in winter. Jake rolls one over and a centipede flicks out, quick as an eel.

Across a stretch of boardwalk we reach the Plants Brook, which bustles through New Hall Valley on its way to the River Tame and, eventually, the North Sea. Its course is marshalled by willows and the occasional alder.

The cascading song of willow warblers mirrors the rhythm of the stream, while the metronome-like chiffchaff marks time in the background. One warped ancient willow, bent double with age, is another favourite climbing tree. In December, the children found a clutch of vapourer moth eggs clasped to its gnarled old bark and they continued to check them patiently until last week they found they’d hatched into miniscule caterpillars; full stops morphed into commas.

The children tumble into the stream. Every dent in the bark, every patch of pebbles and clump of grass has its own name and story for them: the golden pool; the harbour where they launch leaf boats; the island where they dig rivulets in the silt. Once, Danny found a fish inside a discarded glass bottle.

Their bond with the landscape makes this place special. It doesn’t have to be panoramic, secluded or even litter-free; they just need trees to climb, flowers to inhale, minibeasts to spot, stories to tell. Every child needs these; every child needs the chance of a special place.

What the judges said

Gillian Burke: "One of the stronger entries with good field knowledge and evocative descriptions of numerous plants and animals, great and small. A wonderfully descriptive opening elegantly marrying human-made features with the landscape. Social history layered with natural history helped to portray this urban wildlife oasis."

Nicola Chester: "Lovely intimate and imaginative detail in the description of nature: 'bonfire bronze' woods, the 'witches cackle' of a green woodpecker, vapourer moth eggs: the children's names and stories for everything that bonds them to a place, no matter that it might not be 'panoramic, secluded or even litter-free' it's what makes naturalists of us all – something every child has a right, but not access too."

Meet Amy Fox

Name: Amy Fox

Age: 39

Based: Birmingham

Work: I'm a stay-at-home parent to three children – Joey, aged nine, and six-year-old twins Danny and Jake, whom we home-educate.

Is the nature on our doorstep sometimes overlooked? Yes! I think there often seems to be a perceived dividing line between "us" and "nature" – as if nature is something that exists "out there" in reserves and beauty spots: isolated little islands that we have to make a special trip to visit. Fortunately, there is no need; nature has no intention of keeping in its place. We once watched a kingfisher flying under Spaghetti Junction.

Do you find it rewarding to experience nature with children? Absolutely! When you're with children, the most familiar, overlooked nature becomes fresh and exciting.

What inspired you to enter? I've always loved writing but in recent years have struggled to find the time and confidence, so I wrote this entry as a personal challenge to just get something done.

What would you like to explore in your nature writing? I enjoy celebrating the ordinary and overlooked.

What are your favourite places? I love the coast, especially north Cornwall, but that's a difficult question to answer because I think everywhere has its own local character and beauty.

New Nature Writer of the Year 2022: highly commended (two of three)

The Oglet

It is there. I knew it would be. It always is. At first invisible, a sudden movement in the hawthorn and there perched atop the bush is my quarry, launching its scratchy song to the world. My first whitethroat of the year. These choristers are here every spring at the Oglet, my special place.

The Oglet – or, in Scouse vernacular, The Oggie – is called the last piece of countryside in Liverpool. It is a jellyroll quilt of parallel habitats that draw people there. Fields, alongside lines of scrub, merge with clay cliffs that slip and slide towards the mighty River Mersey. Liverpool John Lennon Airport’s runway marks the northern boundary, while the river, with its RAMSAR and Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) status, delineates the southern edge. These two compass points define a peri-urban openness abundant in biodiversity.

Oglet means ‘oaks by the water’. Oaks are still there, ancestors of oak woodland that persisted until Anglo-Saxon times. The trees cool the visitor in times of heat, or bequeath acorns for marauding jays. Oak apple galls are witness to wasps they have hosted, just one of many insects the trees harbour. Hawthorns provide sanctuary for passerines, while insects welcome scrub plants as their domain. Towards the shore, water dominates. High spring tides pound the cliff toe, gnawing at the clay. It is borne away to furnish new river sediment. Tenacious coltsfoot emerges among eroded clays and wrens skitter through marginal vegetation.

Today, the Oglet is seaside, countryside, and playground, a jewel in a peri-urban fringe. To many it is refuge from urban challenges. Photos show children playing in fields, or paddling in the river. Mudlarking youngsters scrabble for treasure, retrieving clay pipe stems, remnants of days when salt was refined down here. Two boys feature in a black and white photo, looking as though they have just emerged from a quick swim in the Mersey. Their postures show they imagine they are ‘cool’.

Every visit brings joy and fascination. There is poetry here: sights, sounds and rhythms of seasonal change

Every visit brings joy and fascination. There is poetry here: sights, sounds and rhythms of seasonal change. In autumn I search fields for fieldfare and redwing. Oglet is rest and refuge for these Viking voyagers. Late spring sees me wandering the scrub, searching for cuckoo flower on which might glue orange tip butterfly eggs. The iridescent jade mantle of a Thick-legged Flower Beetle catches my eye. I sit and gaze on its beauty. I know that, like my whitethroat, swallows will return to nest in a barn nearby. At dusk I watch the gentle quartering of a Barn owl, fields and scrub its kitchen.

Close to the high tide line a sea-log rests, a large trunk stranded by a storm, my vantage point. My feet tickle the beach with its pebbled veil of sandstone, granite, limestone and quartz, moulded by time and water. Glassy shards, etched by sea and salt, and fragments of bladder wrack merge with pebbles, while

Anthropocene nurdles lurk unseen, future fossils to persist long in Oglet’s sands.

Most times I sit on the log, but occasionally prostrate myself along its length, log and I becoming one. Aircraft power above me, distant industry hums, but I inhabit a different realm. Salt-laden breezes calm and caress me. At those moments, I am Oglet. I am gentle tides that nibble the shore, or storming waves that undercut cliffs. I am dunlin fringing the shore, twisting in their beguiling dance, or I lurk with ringed plover hunkered down on pebbles, looking like Mothers Superior monitoring their charges. Nature’s mindfulness reigns here.

There can be drama at the Oglet. A clash of wings and a tumbling of feathers alert me to a battle. Two kestrels fighting: a windhover war of wills. Landing on the ground, they pause wingtips touching. The female is forced onto her back on the ground. Is her supine submission terminal? She fights back. It is vicious and she is floored again. The male kneads her breast. His vivid yellow feet and black talons are capable of destruction. Will a kill ensue? As if reading my thoughts the female rallies. Wings clash. Then it is over. The birds part and fly off to different cliff top refuges. Peace is restored.

Airport expansion now threatens the Oglet. Much of Liverpool’s last piece of countryside will be lost to those who love it. For now I treasure every moment there. How long will my whitethroats sing?

And what of those boys in the old photo? Two boys, forged by Oglet, rich in talent, who could not know what their futures would hold. In time would they, Paul McCartney and George Harrison of Beatles fame, remember how Oglet was special for them? I wonder if George’s guitar will now ‘gently weep’ for Oglet.

What the judges said

Gillian Burke: "Wonderful field knowledge and writing. I only I wish I had known who the boys in the photo were (George Harrison and Paul McCartney). The reveal in the last sentence didn’t give me enough time imagine these cultural icons as little scruffy lads playing in nature. An easy fix to keep this piece of writing alive."

Nicola Chester: "Wonderful descriptions of a peri-urban jewel that means so much to so many: playground, refuge; the bladder wrack and plastic nurdles – a sense of a place in time, absorbing human history, detritus, as well as wildlife – the visceral kestrel fight and the identity of the boys in the photograph illustrated this beautifully."

Meet Jennifer Jones, writer of our final highly commended entry

Name: Dr Jennifer M. Jones

Where do you live? In south Liverpool, North West England, a fabulous city, but I guess I might be biased.

Work: I am a retired university lecturer in soil science, but became an Honorary Research Fellow on retirement, so can still explore the wonders of soil.

What did you choose to write about the Oglet? Oglet might be thought of as an edgeland. These are often the overlooked places yet, from a nature perspective, they are the more valuable for that.

What inspired you to write about nature? Because I am passionate about the natural world and want to share that with others.

Have you ever trained in nature writing? I am just completing an MA in Nature & Travel Writing at Bath Spa University. It has been the most exciting adventure I could ever have undertaken.

Would you like to do more nature writing? Absolutely. I want to write, write and write! I am currently waiting for a publisher to snap up my work in progress, A Teaspoon of Soil, which is a celebration of all that soil does for us. I am also working on a book about soil for children.

What would you like to explore in your nature writing? I want to write about unusual places, eg edgelands, because I want to help people to see that nature is all around us, often in the most unexpected places.

What are your favourite places to enjoy nature and landscape? Oh goodness me, so many to mention. With a surname such as Jones, it’s probably not surprising that I love Wales. I particularly enjoy visits to the Great Orme in Llandudno, where both the birds and flora are fabulous.

• Thanks to all three of our judges, Gillian Burke, Nicola Chester and Cal Flyn.