On the western coast of the Scottish island of Mull, beneath the brooding volcanic massif of mighty Ben More, lies one of the wildest environments in the British Isles.

A single-track road gives way to a logging track at the hamlet of Tiroran, navigating the southern side of the peninsula along Loch Scridain. The six-mile stretch of headland between here and the sea is known simply as ‘The Wilderness’. It’s a fitting description of this trackless terrain characterised by deserted beaches, sparse coastal undercliffs and stunted trees beneath stark basalt terraces.

Fionn and the red giant

This is a land of legends, where the great Irish hunter-warrior Fionn mac Cumhaill (Finn McCool) is said to have constructed a series of stepping stones between Ireland and Scotland. This ‘Giant’s Causeway’ allowed Fionn’s deadly Scottish rival, the Red Giant Benandonner, to cross the sea after Fionn decided to pick a fight with him.

Seeing his adversary’s size and strength up close, a quaking Fionn hid in a cot while his clever wife Oonagh unnerved Benandonner with lurid tales of her husband’s strength and bravery. Benandonner made his excuses and fled back across the causeway, after which both giants tore it up to avoid another standoff, leaving just a few remnants of the hexagonal cobblestones on both sides of the sea, as well

as on the Isle of Staffa just a few miles off the coast of Mull.

Geologically, this explanation is commendably accurate, as identical hexagonal columns of volcanic basalt to those found at the Giant’s Causeway, across the water in County Antrim, are visible on the tip of Mull’s Ardmeanach Peninsula.

Molten Mull

Something of a geologist’s paradise, the terraces and columns of Mull’s west coast are thought to have formed 50–60 million years ago, when the island was torn from the North American supercontinent and molten lava poured from a string of fissure volcanoes lining the fault line. Some of these lava flows came into contact with water, cooling quickly to form the characteristic hexagonal columns found on both sides of the North Channel.

It was while exploring and mapping these strange crystalline formations just over a century ago that geologist John MacCulloch stumbled across a fossilised tree. Today, the 12-metre high fossilised trunk of an ancient conifer – a relic that is sometimes named after MacCulloch – remains visible to those prepared to make the 17.7km round trip on foot. And what a trip this is: truly one of the wildest walks in Britain.

Sparse and spectacular

It’s just a short hop from Oban across Loch Linnhe to Mull, the second largest of the Inner Hebrides islands after Skye. Mull is half the size of its northerly neighbour, with only a quarter of the population and far fewer visitors, so the Ardmeanach isn’t its only expanse of wilderness waiting to be explored. Across extensive swathes of this unassuming island, the natural world has asserted itself. Otters are a common sight on the foreshore, and offshore, dolphins, basking sharks and whales are regular visitors.

Red and fallow deer roam wild on the uplands of the island’s interior, while the Ardmeanach Peninsula is home to a ragtag clan of feral goats. And overhead, above the huge sea cliffs, native golden eagles and reintroduced white-tailed eagles majestically soar. White-tailed eagles are more gregarious than their slightly smaller cousins and, in spring, when many of the island’s resident pairs are busy feeding their young, the chances of seeing one of these avian predators wheeling above Loch Scridain are high. If you’re lucky, you might even get close enough to stare into their piercing golden eyes, from which one of its Caelic nicknames derives: ‘iolaire suile na grein’, meaning ‘the eagle with the sunlit eye’.

On the trail

While essentially flat, the walk out to the Fossil Tree is a demanding hike over rough terrain. Navigation is straightforward, but the route includes some exposed traverses on narrow ledges.

There are waterfalls to negotiate after heavy rain and a 10-metre vertical descent down a rusty iron ladder to reach a wild and isolated beach, and it’s here, embedded within the foot of the cliffs, that you’ll find the Fossil Tree.

1. Forest to sea

The walk starts from the little car park in a paddock to the right of the road beyond Tiroran House, heading west along the forest track towards Tavool Outdoor Centre.

The first few miles involve a string of short climbs and descents though pleasant little woodland dells before heading out on to the lonely coastline beneath the 432-metre summit of Bearraich. Walk past Daisy’s Cairn, commemorating Daisy Cheape, who drowned in the loch in 1896.

4. Steady as you go

From here, the going gets really rough. The path drops down to the beach – and can be briefly impassable on the highest spring tides – before ramping up on to the basalt cliffs, where it narrows to little more than a sheep track.

3. The Rosette

Below you on the rocky foreshore, look out for the Rosette: a formation where the basalt columns have collapsed outwards into an almost perfect circle. It’s thought this landform was caused by lava engulfing another tree which decomposed long ago, leaving ‘spokes’ of basalt radiating out from the ‘hub’ where the trunk once stood.

4. Ladder descent

After negotiating a couple of waterfalls, the path ahead abruptly disappears. A short scramble downhill brings you to a fixed metal ladder that descends to the beach some 10 metres below.

5. Tree in the rock

After nearly half a mile of tough going over the boulder-strewn beaches at the foot of the cliffs, the unmistakable outline of a tree appears in the rock, veiled by waterfalls and encased in hexagonal basalt columns – the very same that are found across the water at Fingal’s Cave on the island of Staffa, as well as at the western end of the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland.

Standing on this deserted headland, with only a few shy red deer peering from the terraces above the beach for company, this atmospheric place really does feel like a lost world. The elemental forces that shaped this rugged landscape are still at work, and echoes of the myths and legends of the past linger among the caves, boulders and cascades that characterise this primal corner of west-coast Scotland.

Map

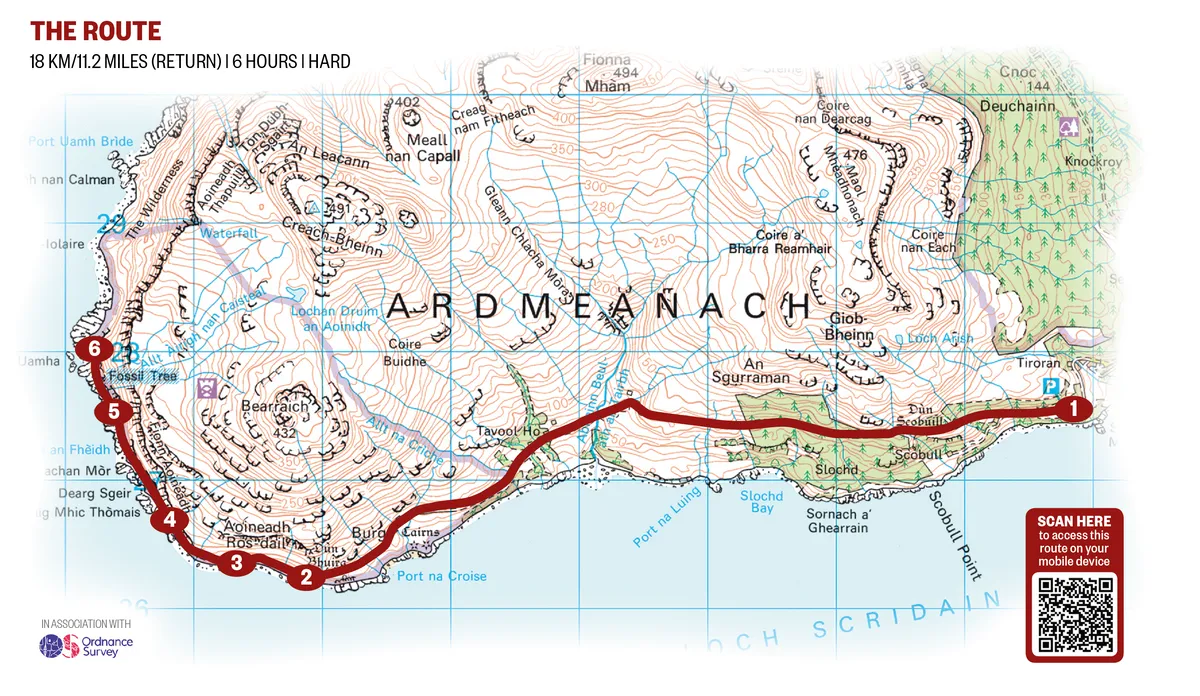

Click on the map below for an interactive version of the route