In the past, trying to uncover our family connections to the countryside would have involved trips to archives, but now, with more and more information going online, it has become much easier for anyone with internet access to explore their family’s rural past.

The great thing about exploring your family history is that you can find out exactly what they did and how they fitted in to the rural economy. Our love of the countryside can be enriched by understanding how previous generations lived and worked there. A beautiful village can be admired by anyone, but if you explore somewhere your ancestors lived and visit the church where they once worshipped, you will experience a much deeper sense of connection.

Here is our expert guide to tracing your rural family tree, including how to begin, which records to check, and all the digital resources you need.

Discover more about your ancestors at our sister title, whodoyouthinkyouaremagazine.com. Good luck!

Main image: Publican Peggy Powell, July 1949./Credit: Don Price/Fox Photos/Getty

How to discover your rural family tree

Step 1: Talk to your family

The first step for anyone wanting to explore their past is to talk to your family and write down what you know already. This often gets overlooked by people who want to jump straight online. Talk to older generations, siblings and cousins to find out what they know already about your family. A digital family tree can be a handy way to keep track of your discoveries. You can download free software, such as Gramps or RootsMagic Essentials, but there are also easy-to-use online family-tree builders on genealogy websites such as Ancestry and Findmypast that you can use for free, although you have to register with the site first.

Step 2: Check the Census records

There is something magical about seeing records of your ancestors at home with their families, and census records let you do just that. The most recent available census is 1911 – although in 2022 the 1921 census will be released, on Findmypast for English and Welsh records and ScotlandsPeople for the Scottish census. Hopefully your initial conversation with family members will have given you enough detail to search for people on a subscription website or you can try the free website FamilySearch, although you won’t see the actual census images there. Most libraries offer free access to Ancestry, so if you are on a budget, try that option.

The 1911 census is the only one where the schedules filled in by the head of the household have survived so you will see your ancestor’s handwriting. Before that, the records available are the books compiled by the enumerator. These 10-yearly records will hopefully take you back to the 1841 census. This early census is not as helpful as later ones as it didn’t ask for much detail about where a person had been born and adult ages were rounded down to the nearest five years. It also didn’t ask people what their relationship to the head of the household was, so you have to guess who is who. Abbreviations were also used for most occupations. In fact, it’s where the term ‘ag lab’ for an agricultural labourer came from. Retracing the decades, you can follow your family and see what occupations they had. The census can also give you clues that will lead to birth, marriage and death records.

Step 3: Look at civil registration

Before civil registration began in 1837 for England and Wales and 1855 for Scotland, vital events were recorded by the church. If someone was born, then it was assumed they would be baptised and a record would be created. Marriage was the same and burial records marked a death. However, a desire for more accurate, centralised records resulted in the introduction of civil registration. These are the birth, marriage and death certificates that form the backbone of family history.

If you are researching Scottish family, then you can order these records from ScotlandsPeople as a digital file for just £1.50 each. For England and Wales you need to go to the GRO website where you can either order a certificate that will be posted to you for £11 or pay £7 for a PDF via email (selected births and deaths only). These records can help you uncover a woman’s maiden name so that you can find her family on earlier census records or tell you the name and occupation of the bride and groom’s fathers enabling you to step back a further generation, or give a cause of death that will help complete an ancestor’s story.

There is an extra fee to pay if you do not have the GRO index reference details, but they are easy to obtain via FreeBMD as well as subscription websites. The GRO also has its own free indexes for births and deaths, which include some additional information such as mother’s maiden name and age at death.

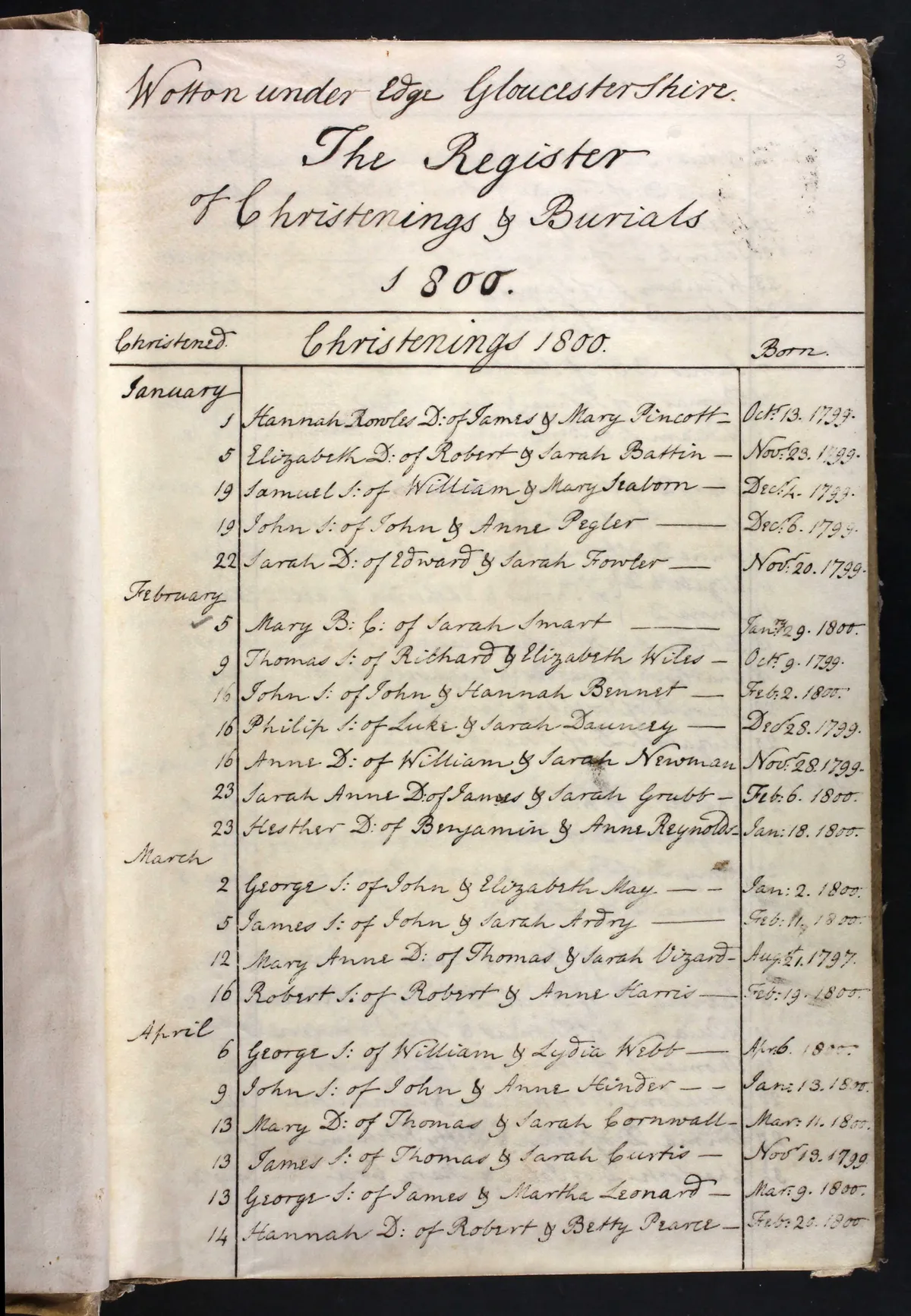

Step 4: check parish registers

Church records can go all the way back to the 16th century but they also continued after civil registration and many of them are now being digitised, making it easier to instantly access them. Subscription sites usually offer digital indexed copies of the original records, while websites such as FreeREG and FamilySearch offer free indexes compiled by volunteers, usually without images. Some areas of the country you will only find on a specific website, whereas others, such as Norfolk and Wales, are covered by a number of sites.

A simple way to uncover online records is to search for a county followed by ‘parish registers’ and see what comes up. If a lot of your family came from a particular county, this could help you choose which website to subscribe to. There’s something wonderful about browsing through the pages of an old parish register. You will find your family among their neighbours, both rich and poor. If you are really lucky, you might find a rector who added his own comments about villagers or local events in the margins.

Step 5: Look at historical directories

Trade directories were ubiquitous from the late 18th century to the early 20th century. Plenty have been digitised and can give a window into rural life. Try the free collection at specialcollections.le.ac.uk Even if your ancestors aren’t named, directories often included descriptions of villages, details of local farming and can reveal the occupations of those who lived in an area, presenting a picture of local cottage industries and prominent families.

Step 6: Search the newspapers

The digitisation of local newspapers has really transformed family history searches and millions of pages can now be accessed via the British Newspaper Archive (available to Pro subscribers on Findmypast). If your ancestor was caught poaching or caught behind at the village cricket match, you will find them recorded. Even if you can’t find someone by name, search for the village they lived in and filter by the time they lived there. You can find out about good harvests and bad, local disasters and village celebrations, all of which would have been experienced by your family.

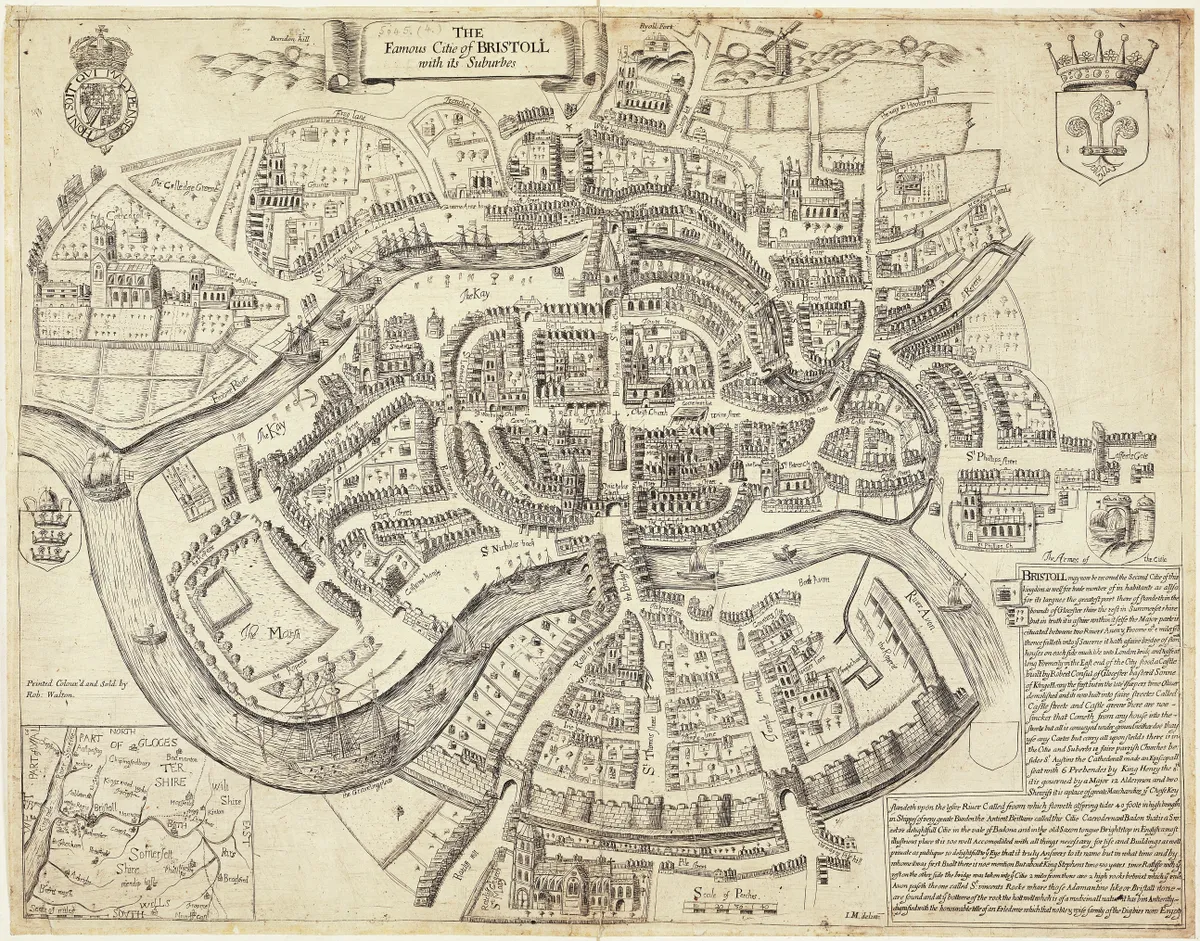

Step 7: Check out relevant maps

Once you know an area where your family lived, the chances are you can find a historic map online; you may even be able to track down the exact piece of land your ancestor farmed. The National Library of Scotland has digitised a huge number of historic maps that cover the entire UK and old-maps.co.uk also has national coverage. Know Your Place is a great example of a regional collection of maps that cover the West of England.

Look out as well for tithe maps which were created in the mid-19th century, when surveyors had to calculate the value of land and who owned it. Previously landowners were obliged to pay the local church 10% (a tithe) of the produce or income from their land, but in 1836 the Tithe Commutation Act simplified things with a fixed payment system. Tithe maps are gradually going online, with a complete collection of Welsh maps available at places.library.wales and those for West Yorkshire at wytithemaps.org.uk. Subscription website TheGenealogist is gradually building up a national collection. The maps come with documents (apportionments) that list who owned the land, who occupied it and short descriptions including names of fields, details of buildings and crops.

Step 8

Take it further

The resources mentioned above are all available online but there are many others tucked away in archives, some now getting digitised, that will reveal more about your rural ancestors. Once you’ve uncovered names and places, you can start looking for things such as farm diaries and estate records. The seasonal nature of agricultural work means that many of our rural ancestors would have relied on parish support during hard times. Many of these records detailing payments made out (sometimes items such as boots or firewood) can be found in parish accounts deposited at record offices. Parishes did not want to support anyone they did not legally have to, leading to a complex system for monitoring who was settled in each parish, along with attempts to uncover the fathers of illegitimate children. This resulted in a wealth of records that can also be explored in record offices, with some now online.

Ancestry resources

Commercial websites for family tree building

Huge collection of records including exclusive content for some counties. Good family tree builder that lets you share research with others.

Another genealogy giant with exclusive content for some counties. Includes millions of pages of newspapers if you take out a Pro subscription.

Pay-as-you-go website offering the majority of records you will need for Scottish research.

Smaller subscription website but includes some exclusive records, such as tithe maps, along with the staples such as census records.

Free websites to help trace your family tree

A global collection of records, some with images. Also has a useful Research Wiki.

A central hub leading to three useful databases.

FreeBMD will supply the reference you need to order birth, marriage and death certificates.

WhoDoYouThinkYouAreMagazine.com

Read tutorials on all the main record sets and keep up to date with new records going online.

Places to visit to help track down your ancestors

The Museum of English Rural Life

A museum, library and archive in Swindon with a large collection of farm diaries.

The National Museum of Rural Life

Based in East Kilbride, Scotland, the museum has a large collection of farm machinery.

Main image credit: Don Price/Fox Photos/Getty