The British countryside is rich in history with many locations providing a treasure trove of precious artefacts that have helped historians uncover more about the history of Britain and paint a picture of how our ancestors would have lived.

According to a report by the British Museum, during the Coronavirus pandemic more people than ever have discovered precious artefacts in their gardens and local area with more than 47,000 ‘treasure’ finds recorded in 2020. These finds have included two significant coin hoards, a Roman furniture fitting and a seal matrix thought to have been used by a bishop from the Medieval period.

The British Museum’s Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) report recorded a huge boost in garden finds and in digital recording during the first lockdown when metal-detecting was prohibited or restricted.

Three major artefacts found during the 2020 lockdown

Coin hoard

63 gold coins and 1 silver coin of Edward IV through to Henry VIII, and deposited in about 1540, were uncovered in the New Forest area, Hampshire as the finders pulled out weeds in their garden. Ranging across nearly a century, dating from the late 15th to early 16th centuries, the hoard includes four coins from Henry VIII’s reign, unusually featuring the initials of his wives Catherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour. The total value of the coins far exceeds the average annual wage in the Tudor period, but it is not yet clear whether this was a saving hoard which was regularly deposited into or if the coins were buried all at once.

Seal matrix

Discovered at Dursley, Gloucestershire, was a lead-alloy medieval seal matrix in the name of David, Bishop of St Andrews, identified as David de Bernham (r. 1239-53). The pointed-oval (vessica) matrix shows the bishop standing in his vestments, with a crozier in his left hand. The inscription in Latin reads ‘David, God’s messenger, bishop of St Andrews’. High-status seal matrices are usually made of copper-alloy or even silver. Given the material, and the relatively low-quality manufacture of this piece, it is thought likely that this is a contemporary forgery, perhaps used to authenticate copied documents.

Roman furniture fitting

A copper-alloy Roman furniture fitting, found in Old Basing, Hampshire, and dating from c. AD 43–200. It is decorated with the remarkably well-preserved face of the god Oceanus, including intricate seaweed fronds framing the god’s face, beard and moustache. Tiny dolphins beneath each ear swim down towards the god’s chin, whilst serpentine creatures rest on either side of Oceanus’ temples – marine motifs related to the god. So far, no close parallel has been identified among the decoration on household fixtures and fittings for chests, couches or doors of this period, making this item seemingly unique.

The report also shows that an incredible 81,602 archaeological finds were recorded in 2019, an increase of over 10,000 on the previous year, bringing the total on its Portable Antiquities Scheme database to well over 1.5 million objects.

These precious treasure finds provide a vital link to the history of Britain and can be of huge cultural and historical importance.

Our expert guide explains how to hunt for precious artefacts in the UK and some of the best places to search, plus an overview of famous treasure finds. We also look at the legality of searching for treasure and what you need to do if you do hit gold and find a precious artefact.

How to hunt for hidden heritage and natural treasures in Britain: codes of practice and the law

You need permission from the landowner to metal detect on private land in the England, Wales and Scotland. It is illegal to metal detect on protected heritage sites. You can find out more about metal detecting codes of practice for archaeological artefacts and what to do if you discover ‘treasure’ via;

- The Portable Antiquities Scheme (England and Wales)

The PAS database holds information on over 1,514,000 objects, all freely accessible to the public. The Scheme exists to record archaeological finds discovered by the public to advance knowledge and understanding of British history through research and furthering public interest in the past.

In Northern Ireland you will need to apply for a license, and it is a criminal offence to search for archaeological artefacts without one. You can find a guide to the law: communities-ni.gov.uk

Changes to the Treasure Act 1996

Following huge growth in treasure hunting, the government announced plans at the end of 2020 to make changes to the 1996 Treasure Act to protect any finds by law. Under the new rules any artefacts can be defined as treasure if they are of historical or cultural significance.

Under the current law, finds are classified as treasure need to be found to be more than 300 years old or made using precious metals, such as gold or silver.

The aim of this change is to ensure that important artefacts are protected and can go on display in museums so they can be viewed by the public and not sold to private collectors.

- See the Treasure Act 1996 for more information.

Visit the National Council for Metal Detecting (NCMD) for metal detecting code of conduct.

You need permission to pan for gold on private or environmentally protected land; for more details see: britishgoldpanningassociation.co.uk

Remember to take care of tides and rock hazards when searching for fossils and agates, and research restrictions for each area.

Famous precious treasure finds discovered in Britain

Metal detectorists have added a great deal to the knowledge we have about the past. For instance, in 2010 in a field in Frome, Somerset, hospital chef Dave Crisp and his metal detector came across a hoard of 52,000 Roman coins buried in a large pot under the ground. One of the most important aspects of the find is that it contains a large group of coins of Carausius, who ruled Britain independently from AD 286 to AD 293.

Do you dream of what fascinating heritage lies under your feet? Here are some famous cases of artefact-hunters who struck gold, with details of where you can see their precious finds now.

Treasure recorded in the UK

According to the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport treasure report, in 2016, there were 1,116 cases of reported treasure finds. The provisional figure for 2017 was 1,267 making this the fourth year in a row when the number exceeded 1,000.

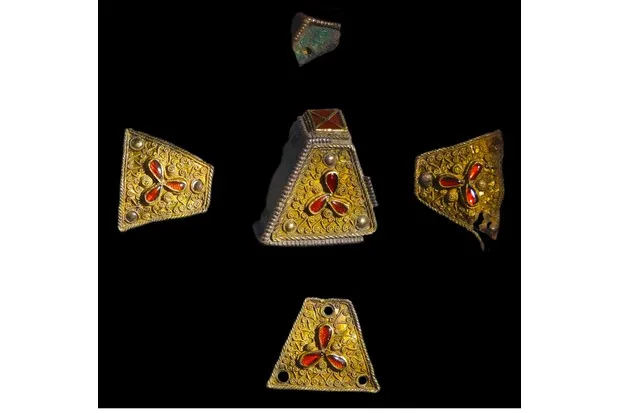

Staffordshire Hoard

BURIED: c. 7th century

FOUND: 2009, near Hammerwich, Staffordshire

The largest collection of Anglo-Saxon gold and silver metalwork yet found, comprising 3,500 items, including 5.1kg of gold. It was discovered by detectorist Terry Herbert when he was searching an area of ploughed farmland. The collection includes decorations from swords and other weaponry, and was valued at £3.28 million.

SEE: Items from the Staffordshire Hoard are on display at Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery. More items are on display in Stoke on Trent and Tamworth – see staffordshirehoard.org.uk for details.

Galloway Hoard

BURIED: c. 1,000 AD (research continues)

FOUND: 2014, Dumfries and Galloway

“My senses exploded, I went into shock, endorphins flooded my system and away I went stumbling towards my colleagues waving it in the air.” This was how retired businessman and detectorist Derek McLennan described his discovery of a Viking arm ring on church land in Dumfries and Galloway, in a BBC interview. His find led to the unearthing of more than 100 ancient objects valued at £1.98m. Described by National Museums Scotland as “the richest Viking-age collection discovered anywhere in Britain”, the hoard included valuable silver ingots, prized arm-rings, a silver pendant Christian cross, brooches, beads and a delicately crafted gold pin in the shape of a bird.

SEE: Items from the hoard were displayed at the National Museum of Scotland in summer 2017, but have now been sent away for an estimated two years for conservation. If all goes well, expects the hoard to be back on display some time from late 2019.

Seaton Down Hoard

BURIED: 4th century

FOUND: 2014, Near Seaton, East Devon

Detectorist Laurence Egerton chanced upon two ancient coins buried just under the surface of a field near Seaton. After further digging his find grew into a staggering 22,888 Roman coins - roughly equivalent to two years’ pay for a middle-ranking civil servant of the day, apparently – and the third largest such hoard ever recovered in Britain.

SEE: the Seaton Down Hoard at The Royal Albert Memorial Museum (RAMM) in Exeter, Devon.

Lenborough Hoard

BURIED: 11th century.

FOUND: 2014, in a field south of the town of Buckingham

Detectorist Paul Coleman found 5,252 late Anglo-Saxon silver coins worth £1.35 million. Read more about Paul's discovery below.

SEE: 1,000 coins from the Lenbrorough hoard are on display at Buckinghamshire County Museum in Aylesbury.

Gaulcross Hoard

BURIED: c. 400-600AD

FOUND: 2013, Near Fordyce, Aberdeenshire

Alistair McPherson was working alongside National Museums Scotland when he discovered a hoard of Roman and Pictish silver in a field – the most northerly find of its sort in Europe. Among more than 100 pieces of silver were coins, brooches and bracelets. Alistair McPherson’s friends now simply call him “the Magnet”.

SEE: the Gaulcross Hoard on display for the first time as part of the exhibition Scotland’s Early Silver, which includes other precious finds. Until 25 February 2018 at the National Museum of Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh.

The Ringlemere Cup

BURIED: 1700 to 1500 BC

FOUND: 2001, Ringlemere Farm, near Sandwich, Kent

Cliff Bradshaw discovered a beautiful Bronze Age golden chalice in a muddy field. The badly-crushed cup, decorated in a cordware style, would have originally stood 14cm high with a rounded base. It is one of only two ever found in Britain. The British Museum bought the cup for £270,000, the money divided between Bradshaw and the landowners.

SEE: The Ringlemere Cup on display in the prehistory galleries of the British Museum in London.

Vale of York Hoard

BURIED: c.927AD

FOUND: 2007, near Harrogate, Yorkshire

David Whelan and his son Andrew were exploring a field when they discovered a finely engraved Viking bowl of silver. Their discovery inspired a full dig that uncovered the largest Viking hoard found in Britain since the Cuerdale hoard of 1840. The 617 silver coins and 65 other pieces of silver items were later valued at Valued at £1,082,000 by the independent Treasure Valuation Committee.

SEE: the Vale of York Hoard: Items from the hoard form part of a touring exhibition, Viking: Rediscovering the Legend, on display at the Djanogly Gallery in Nottingham from 24 November 2017 to 4 March 2018, and after that in Southport, Aberdeen and Norwich. More details from yorkshiremuseum.org.uk.

Roman coins

In 2010 in a field in Frome, Somerset, hospital chef Dave Crisp and his metal detector came across a hoard of 52,000 Roman coins buried in a large pot under the ground. One of the most important aspects of the find is that it contains a large group of coins of Carausius, who ruled Britain independently from AD 286 to AD 293.

Gold and silver artefacts

Metal detector enthusiast Terry Herbert found more than 3,500 gold and silver artefacts in a field in Hammerwich in July 2009 in what became known as 'The Staffordshire hoard'. The vast majority of items in the hoard were martial gear, especially sword and helmet fittings. It is the largest hoard of gold from the period ever found.

900 silver pennies

With the exact location withheld, over a six-year period amateur enthusiasts found over 900 silver pennies on an Anglesey beach. Dates of the pennies ranged from 1272-1307 and while most were English, there were also coins from Scotland, Ireland and some European countries.

A treasure chest

In 1840 workmen hauled a lead-lined chest from the bank of the River Ribble. Inside was over 8,500 pieces of silver consisting of coins, ingots, amulets, chains, rings, cut-up brooches and armlets. It is the largest Viking Age silver hoard found in northwestern Europe.

Gold dollar coins

In 2007, 80 gold dollar coins were found in the back garden of a Hackney property in London. All were $20 denominations known as ‘Double-Eagle’ minted in the US dating from 1854 – 1913. However, they were ruled not to be treasure as the previous owner’s son was eventually traced.

What type of treasure can you to hunt for in Britain, plus best places to look

1

Semi-precious stones

As a meeting point between the North Sea, The Thames Estuary and the English Channel, Kent makes an ideal location for beachcombing. With finds ranging from coins to silverware and even Baltic amber, Kent’s coastline is loaded with far-flung treasures.

2

Message in a bottle

Camber Beach in East Sussex is one of the UK’s best beaches for beachcombing. With finds being anything from semi-precious stones and shark egg casings, to jewellery and messages in bottles.

3

Pan for gold

For gold panners of all levels and experience, the Museum of Lead Mining in Dumfries & Galloway offers potential prospectors the chance to go panning for real gold that you can take away with you.

The Dolaucothi Gold Mines in Ceredigion, though no longer a working mine have been in use since Roman times. Set amid the hillsides of the Cothi Valley you can try your hand at gold panning in the sifting troughs here.

4

Silver-lead

The Silver-lead mine in Llywernog was initially established around 1742 and by 1842 the mine was operating successfully. The mine gradually became less and less productive until it closed around the 1880’s. Today it is an independent museum where you can work the mine material for Silver-lead and keep what you find.

5

Precious metals

The Highlands of Scotland have long been known to be rich with precious metals. In fact the largest piece of gold ever found in Scotland came from this region. Perthshire’s Gold and Gem Panning Centre and nearby Loch Tay are no exception and offer excellent locations to hunt for gold and silver.

6

White quartz

Northern Ireland has been said to represent one of the most complex and varied areas of geology in the world and as the resulting gold from these geological processes occurs in veins of white quartz, panning is still the best method of finding it.

7

Marble

In Torrin, situated near Elgol on the picturesque Isle of Skye, marble is quarried from the limestone-rich terrain. Skye marble – a genuine marble - has a distinct appearance due to the particular geology of the area in which limestone and granite come in to contact with each other. Many other minerals and precious stones are found in this area.

8

Rare smoky quartz

With the exception of the famous Leadhills and Wanlockhead deposit, the mineralisation of Scotland’s Southern Uplands is small in scale but varied and includes a number of amethyst deposits found in granite intrusions. In 2009, small palm-sized plates were discovered in rare smoky quartz near the summit of Screel Hill.

9

Jasper

Jasper can be found amid the volcanic hills of the Campsie Fells, just above the small village of Blanefield in Scotland. One of the more famous sites, specimens from here are generally blood red or yellow and prized by lapidaries for its fine grain.

10

Whitby jet

The ancient Lias Sea (nowadays the area encompassed by the North York Moors National Park) created the perfect conditions for the formation of jet. Nowadays it can be found exposed in the cliffs and shores near the town of Whitby in small, fractured and worn pieces. Whitby jet is said to be the best quality jet available.

11

Blue John

Blue John, also known as Derbyshire Spar or Derbyshire Blue John can only be found in the Castleton mines in Derbyshire. Mined during the 19th century for its ornamental value and shipped across the world, it is now considered scarce and only a few hundred kilograms are mined per year. The name derives from the French ‘bleu et jaune’ (blue and yellow), a reference to its colour. Take a walk from Castleton to the mines.

12

Amber

Amber is often found in the shingle along the Suffolk coastline and the best time to do so is said to be after a storm, when new exposures can occur. The amber found in this area is known as ‘Hastings firestorm amber’ on account of the unique characteristic and colour produced by localised forest fires that took place during the Cretaceous period.

13

Gemstones

Near the village of Elie, in the county of Fife lies Ruby Bay. The name is a bit of a misnomer as the clear brownish-red gemstones found along its beach are actually pyrope garnets coloured by chromium. Embedded in the volcanic rock that forms the shoreline, the gemstones are displaced by the action of extreme weather and are best found after a storm or during the spring tides in the shingle.

14

Agate

Just north of Dundee, Angus on the east coast of Scotland is arguably the countries most famous agate location. Though the locality is now covered up, it was made famous by the Usan blue hole agates – typically brilliant inky blue and white coloured agates – that were discovered, in the 19th century.

15

Sapphire

The rarest of Scotland’s gemstones, sapphire can only be found on the protected Isle of Harris — the site is the subject of a protection order banning their removal. These dark blue gemstones are of a particularly high quality, as they need no heat treatment to bring out their rich colour, unlike sapphires found outside Scotland.

16

Smoky quartz crystal

Located in the central highlands of Scotland, Loch Tay and the surrounding region was a centre of glaciation during the last ice age and as a result it is rich in mineral wealth deriving from the granite-based landscape, including many varieties of quartz; notably Cairngorm quartz, a form of smokey quartz crystal usually a yellow-brown colour.

17

Sea glass

Brighton’s sand-free shingle beach is an ideal place to look for sea glass. Because of the beach’s popularity, glass will often be discarded on the beach by visitors, and so the chances of finding sea glass here are quite high.

The beaches of Lyme Regis offer an excellent source for finding sea glass. The coarse, stony beaches of Lyme Regis, in combination with the rough Atlantic swells that often reach the shore, have created ideal conditions for the creation of sea glass.

Iona, on the west coast of Scotland is another great place to find sea glass. Looking out over the Atlantic, and practically unsheltered from storms this area’s beaches turn out some fantastic specimens of sea glass.

Exposed to the fierce North Sea, Seaham on the Durham coast is a good place to look for sea glass. The beaches terrain and strong tidal sway help to create ideal conditions for sea glass production.

After stormy weather, the beaches around Pentewan, south Cornwall and in particular places with headlands which catch the currents, are good places to search for sea glass according to local beachcombers.

18

Fossils

Dinosaur Coast, also known as the Fossil Coast stretches for around 35 miles along the east Yorkshire shoreline, some of the fossils found here are 120 million years old and you can even see dinosaur’s footprints still visible on the beach.

Located on the southernmost tip of East Sussex, the chalk headland of Beachy Head showcases 17 million years of sediment deposition and fossils recorded in the chalk cliffs and surrounding beach.

The 95-mile stretch of the East Devon and Dorset coastline (designated as England’s only natural World Heritage Site in December 2001) is a fantastic place to see some superbly preserved fossil remains ranging from the Triassic period, right through to the Cretaceous. Equally, the Isle of Wight has some brilliant locations such as Alum and Whitecliff Bay respectively.

Finding fossils can prove more difficult at Marloes Bay than at other locations. Consisting of four main geological groups - Skomer Volcanic, Coralliferous, Gray Sandstone and Old Red Sandstone - visitors pass through each group in turn (heading south) until reaching the end of the bay. The Coralliferous Group offers the best chance to view fossils including a wealth of marine organisms.

White Park Bay sits between two headlands on the North Antrim coast. Fossils, though not abundant, are common and if you know what to look for, the beach can reveal a trove of other archaeological evidence, including Neolithic tools.

19

Mines

More an amalgamation of smaller, more ancient mines, Botallack Mine in West Penwith, Cornwall sits atop the cliffs over looking the ocean. There is evidence of tin mining going back as far as the 17th century on this site and visitors can see the ghostly remains of the mine’s buildings still clinging to the Cliffside.

Two engine houses form part of the scattered remains of Wheal Trewavas Mine on the Cornish coast. Perched precariously atop the cliffs, the mine opened in 1834 and a plan of this time shows four copper lodes and one tin lode in operation. Exercise caution on the site and the paths leading to it, as the building are in a ruinous condition.

Unsurprisingly, the East Pool Mine is situated to the east of the village of Pool in Cornwall. Preserved in excellent condition as part of the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape it boasts one of the largest pumping engines in the world and an industrial heritage discovery centre where you can learn about the story of Cornish mining.

One of the most important Bronze Age copper mines ever discovered; the Great Orme Mines are now a fee-paying attraction where visitors can explore the impressive caverns and winding tunnels of the mine on a self-guided tour.

Located in Cumbria, the Nenthead Mines Heritage Centre testifies to the legacy of the mining industry that once dominated the landscape of the North Pennines. Visit Carr’s Mine to learn more about what was once one of the most productive mines in the country, producing lead and zinc over a period of three centuries.

20

Shipwrecks

The Royal Charter wrecked in Dulas Bay on Anglesey in 1859, taking with it 459 lives and a consignment of Australian gold. Many passengers were said to be weighed down by belts of gold. Treasures were rumoured to have washed up on Porth Alerth beach, making local families rich.

Just off Rhossili beach in the Gower Peninsula lies a shipwreck from the 1600’s, nicknamed the Dollar Wreck after Spanish silver dollar coins were recovered from the surrounding sand in 1834.

21

Royal treasures

A caravan of King John’s treasure was famously lost to a rising sea in 1216, while he was attempting to cross The Wash between King’s Lynn and Long Sutton. The treasure supposedly includes crown jewels, jewellery and gold coins.

What's it like to find treasure?

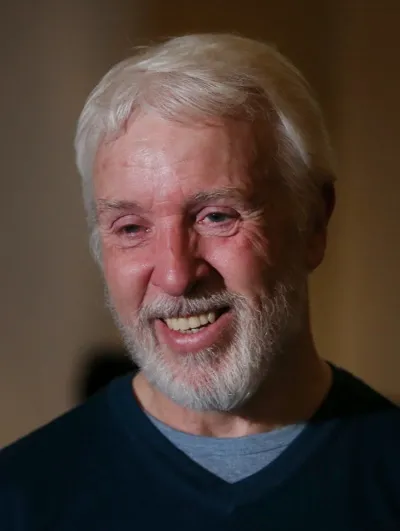

Paul Coleman was in a Buckinghamshire field in 2014 when his metal detector began to beep.

“You can gauge the size of the buried metal by listening to the sound. This was a loud signal, and I could tell the object was quite large, but you can’t really know for sure until you dig.”

So Paul began took out his trowel. As he shifted more clay and silt, the anticipation mounted. “The signal seemed to indicate it was getting larger and larger. By the time I had gone to two feet, I could tell that whatever I was about to unearth was huge.”

At last, Paul struck metal: a humble lead container. He thought it was junk. But then he spotted the bright coins inside, stacked neatly.

Paul had found more than 5,252 silver coins, around 1,000 years old. They bore the faces of their kings: Ethelred the Unready and Canute, who ruled between 978 and 1035. The hoard was unusual partly because the first was an Anglo-Saxon king, the second a Viking; and coins from both are rarely mixed. They were later valued at £1.35 million.

The secret of treasure hunting

Paul’s success didn’t come overnight. “Forty years,” he says. “I’ve been doing this for that long.”

Unsurprisingly, he says that perseverance is the key to metal detecting. “If you put enough time in, you’ll get lucky – you’ll find something really interesting"

The waiting, he reckons, enhances the joy of making a find. "Like angling, or cricket, very little happens for a long time and then you get the big reward. And the time between those moments increases the anticipation.”

Peter Welch runs the 1,000-strong Weekend Wanderers Detecting Club, and was at the scene with Paul when he found the hoard. “Lots of people try detectoring and get disappointed quite quickly when it turns out that it’s not a path to instant riches, that they have to put in the time walking up and down fields,” he says.

The real reward

Some detectorists argue, though, that the real treasure of detectoring is time spent in the countryside.

“People who have taken up and continued detecting tend to appreciate the value of just being outdoors,” says Steve Critchley, a member of the UK’s National Council for Metal Detecting.

Peter agrees: “Some of us are there really to relax, and swinging a metal detector provides a purpose for a walk in the country.”

For Lance and Andy, the main characters in Detectorists, the pleasure of each other's company is also part of the attraction – although of course they would never say so.

But surely all that fruitless wondering gets a little... dull? Paul is adamant: “It’s never boring because, like fishing, it’s the quiet times that make that lucky catch worthwhile.”

Just as well, because there's no guarantee of success, no matter how long you spend looking. “People think I’ve achieved something big," says Pail, "but it’s just a stroke of luck, really.”