Britain's tree cover had steadily declined since the Middle-Ages, and in the early 20th century, extensive tree felling left the country’s timber resources severely depleted.

The First World War changed many things in Britain, and the country’s woodlands were no exception, with the conflict ultimately transforming Britain’s forests. Did you know that just 100 years ago many of the forests we enjoy in England today didn't even exist?

Founded in September 1919, the Forestry Commission began essential work to restore England's forests and woodlands that had been lost during the First World War. Celebrating its centenary year in 2019, our guide looks at the history of the UK's forests and woodlands, wildlife to spot and the best forests to visit.

- Love the woodlands? Get closer to nature at a tranquil forest campsite this year.

History of British forestry during the First World War

At the outbreak of war in 1914, there had been little anxiety about timber supplies, but there was soon a shortage. The Royal Navy found itself in greatest need. It desperately required coal for its fleet, which meant increasing production in coal pits around the country. Essential to prevent the new tunnels from collapsing were pit props – made, of course, from timber.

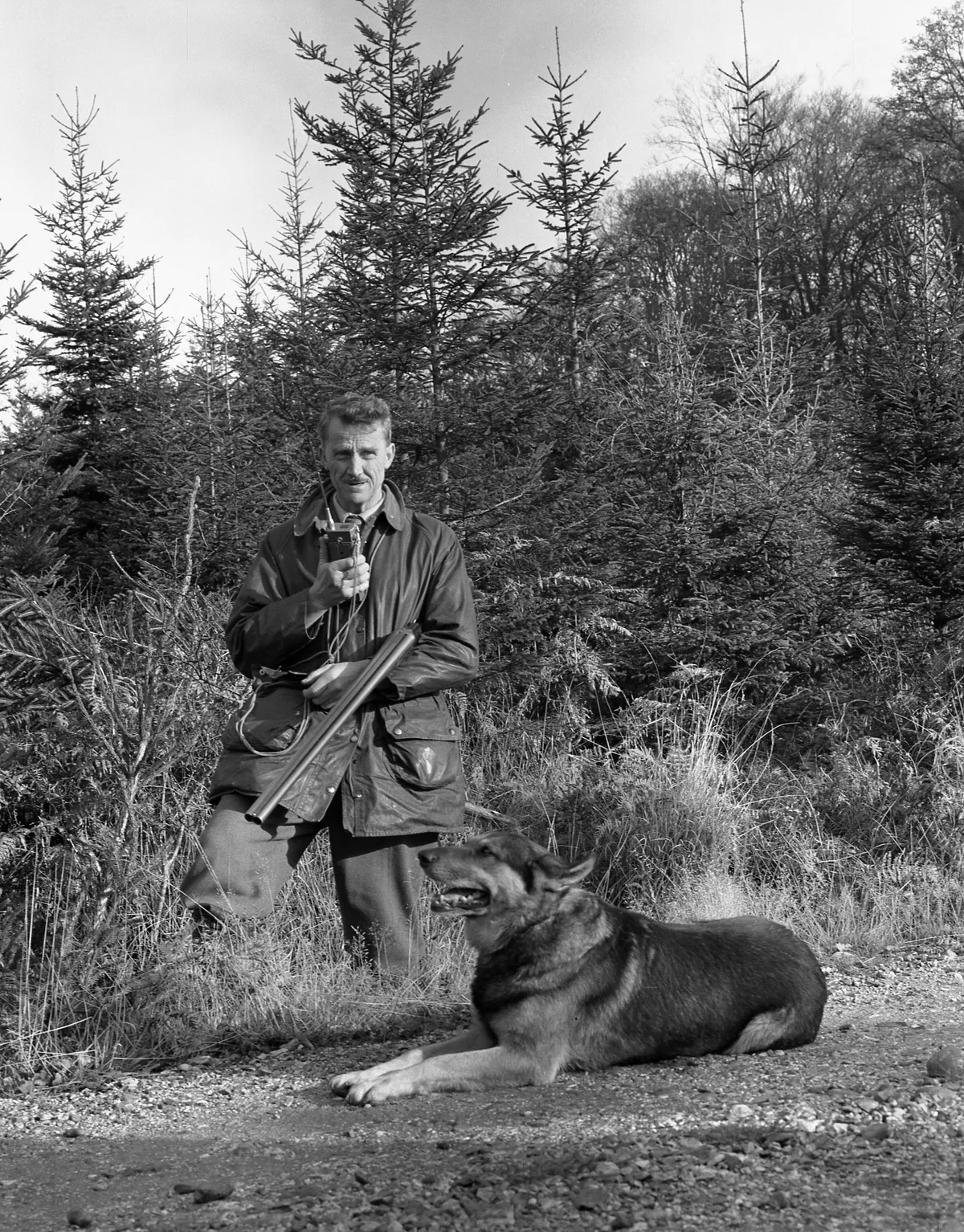

Unfortunately, Britain’s forests were not ready to meet the demand. Scientific, modern forestry – developed in 18th-century Germany and based on careful measurement and management of plantations – had been slow to catch on in Britain. While enthusiastic gentry had long planted trees from around the world, Edwardian forestry had been dominated by wealthy landowners more focused on growing woodlands in which to rear pheasants for shooting rather than for timber production.

With the supply of timber from overseas imperiled by German submarine attacks, the government recognised that vigorous action was required to maximise home production. So, in November 1915, the Homegrown Timber Committee chaired by Liberal MP Francis Acland was established to control the supply of timber across Britain.

Progress was rapid. There were 182 government-run sawmills by the end of 1917, supplemented by a further 40 mills run by groups such as the Canadian Forestry Corps and Women’s Forestry Corps. By 1918, 182,000 hectares of woodland had been felled – an area larger than modern-day Greater London.

Photo gallery: the Forestry Commission through the ages

What does the Forestry Commission do?

The strain of the First World War left woodlands in a state in disrepair, and by 1919, woodland cover was at an all time low of 5%. It was decided that an urgent solution was needed, and on the 1st September 1919, The Forestry Act was passed.

This act created the Forestry Commission – a body that would create woods and forests owned by the state. Things moved quickly and the tenacious Roy Robinson appointed to the key role of technical commissioner. The war had catalysed the introduction of a state forest service and the luxurious forestry traditionally practised on landed estates was now a thing of the past.

Where were the first Forestry Commission trees planted?

In December 1919, the first Forestry Commission trees – a combination of beech and larch - were planted in Devon’s Eggesford Forest by Lord Clinton.

From that moment onwards, the Commission’s estate grew to over 900,000 acres (364,217ha) across England, Scotland and Wales, while the demand for timber increased as tensions in Europe mounted once again.

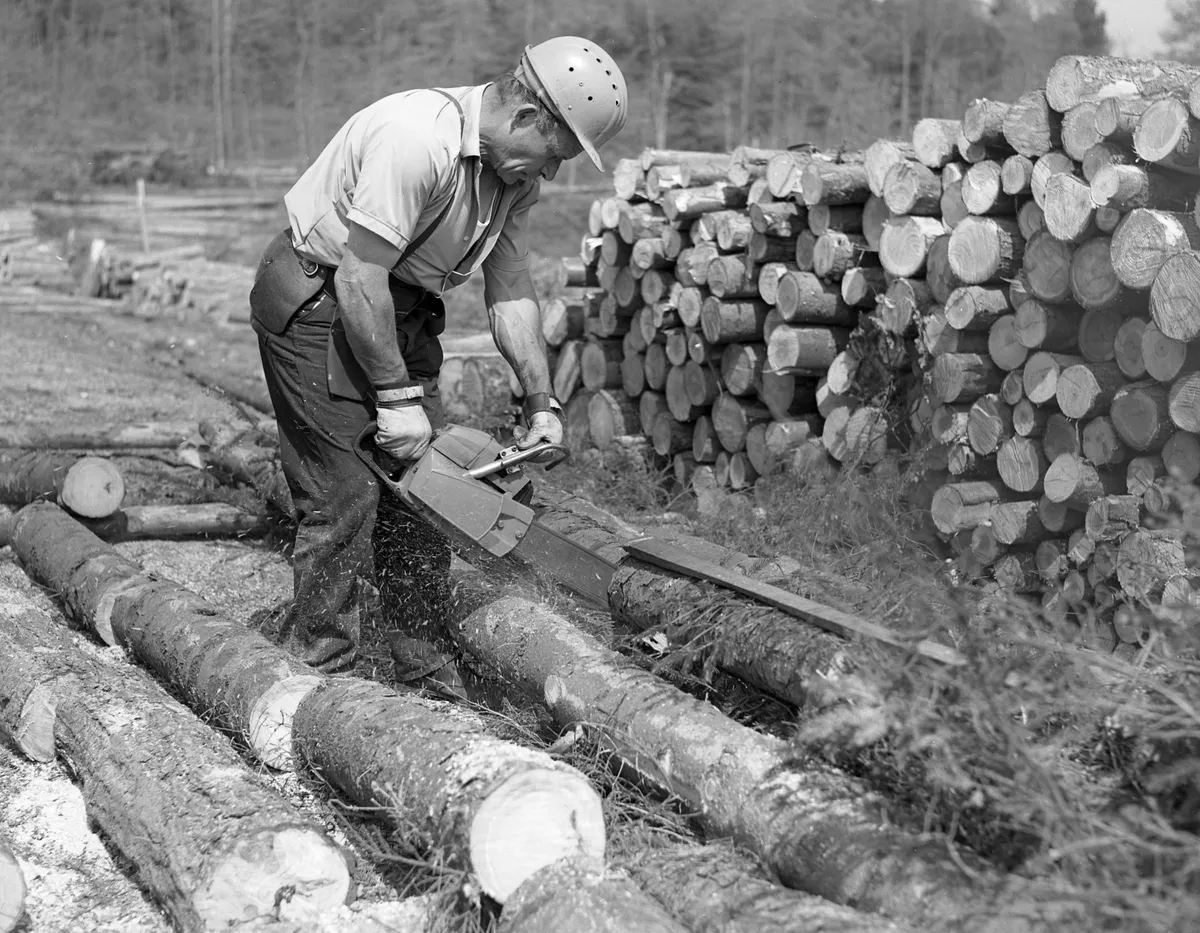

Planting was by hand and felling by axe and saw; in the interwar years, forestry was barely mechanised. By 1939, 4,300 industrial staff worked directly for the FC; the peak in direct industrial employment was in 1954, at 13,600. This number then fell throughout the late 1950s and 1960s, with the arrival of labour-saving chainsaws. Later, mechanical harvesting made felling even more efficient.

By 1939, the FC had acquired 171,000 hectares (659 square miles) of plantable land in England and Wales and 105,000 hectares (407 square miles) in Scotland. It had planted and acquired 189,000 hectares (731 square miles) of coniferous woodland and 26,600 hectares (103 square miles) of broadleaved woodland.

The Second War and demand for timber

The Second World War only reinforced the need for state control of forestry. The war effort once more demanded timber; 11% of all woodlands had been felled by the time of the 1947/9 census. This new planting produced uncompromisingly commercial forests that were modern, regular, efficient and utilitarian. Most planting was in artificial, single-species blocks of conifers. The largest examples were at Galloway Forest Park in Scotland and Kielder Forest in Northumberland; both dominated by fast-growing Sitka spruce.

Meanwhile, private landowners had also been planting similar forests, often supported by the FC, which started paying tree-planting grants in the interwar period, improving these after the war with comprehensive grants for farmers and landowners. (In return, private landowners are obliged to apply for permission to harvest trees, as the FC regulates felling on private land.)

Well before the Second World War, the massive new forests were being criticised by the Friends of the Lake District for blocking public access and for replacing ‘wilderness’ with managed landscapes. The clergyman, schoolmaster and campaigner for national parks, Henry Herbert Symonds, argued that “natural beauty” which provided “emotional resources of escape from the frigid pattern of urban life” was being ruined by the “groping” and “mutilating hands” of the FC. There was an intense dispute in the mid-1930s, with the Council for the Preservation of Rural England negotiating a halt to the afforestation of the central Lake District fells.

Guide to British trees: how to identify common tree species and where to find

Can you spot an oak from a horse chestnut tree? Learn how to identify trees with our expert guide to British trees, plus where to find them.

Also, find out which is the common tree found in the UK.

In its first 10 years, the FC aimed to establish 81,000 hectares of new woodland, and very nearly achieved it. The commission bought land on the open market, or leased it for 999 years.

Most of the land was marginal upland grazing land of relatively little importance for agriculture. In the lowlands, land chosen included heathlands in Hampshire, Sherwood Forest and Suffolk, and huge areas of recently felled woodland.

Now, the Forestry Commission’s main aim is to maintain and enhance England’s forests for people and wildlife; planting a range of species to create forests resilient to climate change and tree disease.

In its centenary year, Forestry Commission England looks after more than 1,500 woods and forests. It undertakes important research on forest establishment and harvesting, mechanisation, herbicides and production control. It has played a vital role in advising landowners about devastating diseases, such as Dutch elm disease in the late 1960s and, more recently, ash dieback, which could kill millions of ash trees over the next 20 years.

The FC is also country’s largest landowner, managing diverse forests, heathlands, moors and urban spaces, and delivers scientific services in support of sustainable forestry.

Who were the Lumber Jills?

By the end of 1941, 3,800 women from the Women’s Land Army were working in woods and forests.

Their work was so important that, in April 1942, the Women’s Timber Corps was established; by the following year, 8,500 women were working for the Forestry Commission and the timber trades. .

Most were felling trees, using large axes and two-handed saws. Once felled, trees had their side branches removed (snedding) and were cut into lengths and stacked ready to be taken by lorry to the sawmill.

The trees were used for pit props, telegraph poles, chestnut railings or tracks (some used during the D-Day landings) and aircraft construction, including the Mosquito. Women were trained for a month before starting work in the woods. Those good at mathematics were selected for forest mensuration, including choosing the best trees for felling and devising extraction routes

Why do we need forests and woodlands?

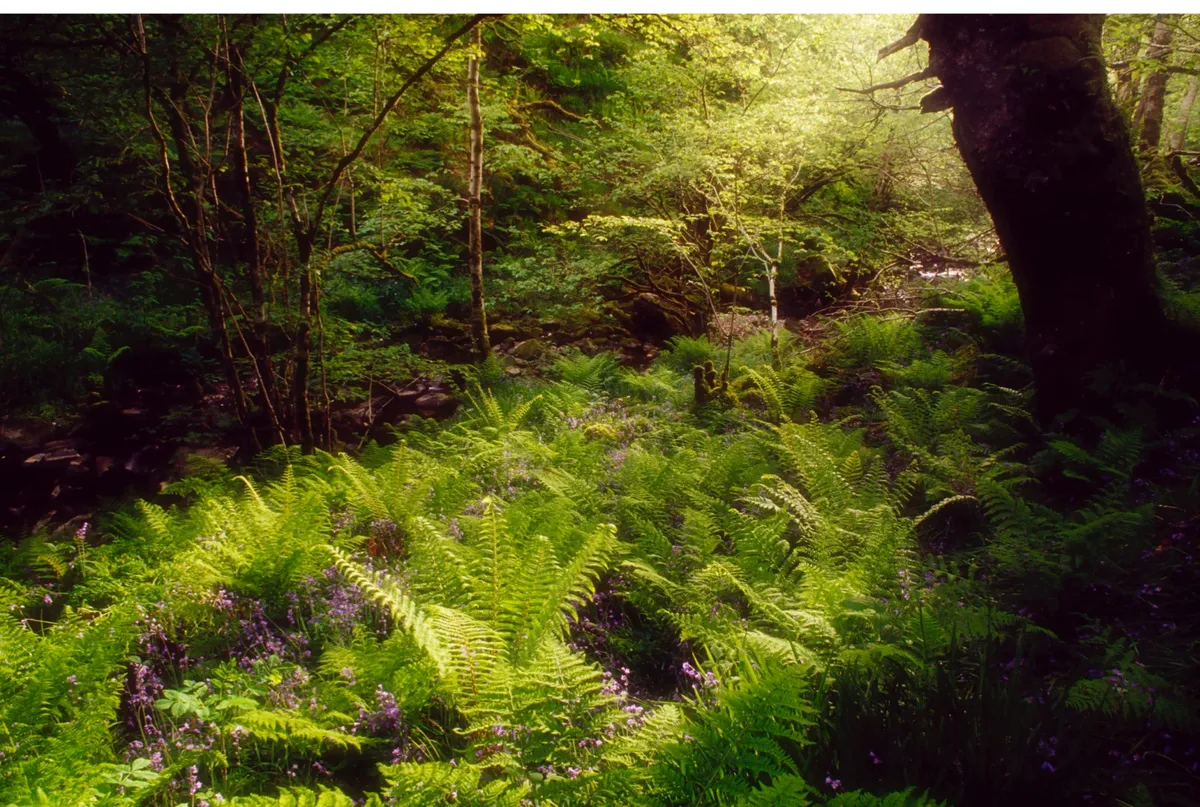

Forests have many environmental and health benefits, which is why they need to be as resilient as possible to the threats of climate change, pests and diseases.

As well as providing sustainable timber, essential habitats for wildlife, and a place for recreation and escape, forests also create cleaner air and prevent flooding.

Studies have also shown that forested areas can have a positive impact on health, finding that just two hours in a forest could lower cortisol (the hormone linked to stress), reduce blood pressure and boost the immune system.

This is the reason why many link forests with a sense of wellbeing, suggesting that woodlands are not only good for physical health, but for mental health too.

Best woodland wildlife to spot in the UK

UK forests and woodlands are the home of a plethora of wildlife species, from bats to pine martens. Some of the most common forest-based species include:

Birds of prey

Goshawks, buzzards, ospreys and red kites frequently visit forests and like to fly over newly planted areas in search of food.

Small birds

Many small birds, like the kingfisher, will be found near forest streams, while others - particularly cuckoos, woodpeckers and goldcrests - remain around the edges of our forest.

Insects and invertebrates

Small insects and invertebrates such as beetles, butterflies, moths and dragonflies are an essential part of the forest - all other ecosystems depend on them.

Owls

Tawny and long-eared owls can be found in a range of forest habitats, but are mainly found in coniferous woodlands.

Guide to Britain’s owl species: where to see and common species found in the UK

The season of darkness and mystery belongs to the owls. Learn more about these nocturnal predators – with our guide to the UK's most common owl species, including where to see and how to identify.

Deer

Roe deer, red deer and muntjac are the three forest-based deer species.

The best forests and woodlands to visit in the UK

The UK is home to spectacular trees and woodlands, from England's largest forest, Kielder, to County Derry’s untouched Banagher Glen. Here’s our pick of the top five forests to visit.

New Forest, Hampshire

Here, the word ‘forest’ refers to its ancient meaning: a royal hunting ground. The forest has no expanse of thick woodland, but vast areas of heather moorland punctuated by New Forest ponies, grazing cattle, deer and red kites.

Baluain Wood, Perthshire

Pull on your boots and step into a reclaimed forest, climbing through trees of golden larch, towering Scots pine and magnificent mountain ash in search of a roaring Cairngorms cascade.

Coed y Brenin, Snowdonia

River Mawddach flowing through the Coed y Brenin forest park in the heart of Snowdonia National Park

Located near Dolgellau, Coed y Brenin is now one of the flagship forests of Natural Resources Wales. Commercial softwood forestry across some 7,650 acres (3,093ha) of Forest Park combines with recreational facilities for mountain-bikers and a network of spectacular scenic trails for hikers, based around the impressive visitor centre.

Banagher Glen, County Derry

Banagher Glen in Northern Ireland is one of very few pieces of forest in the United Kingdom that is just about untouched by human hands – at least as far as deforestation is concerned.

Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire

Take a walk or cycle along one of the Forest of Dean’s numerous trails, passing time-worn stations and former collieries through enchanting ancient woodland.